BLOG - Scissors Paper Stone (SPS)

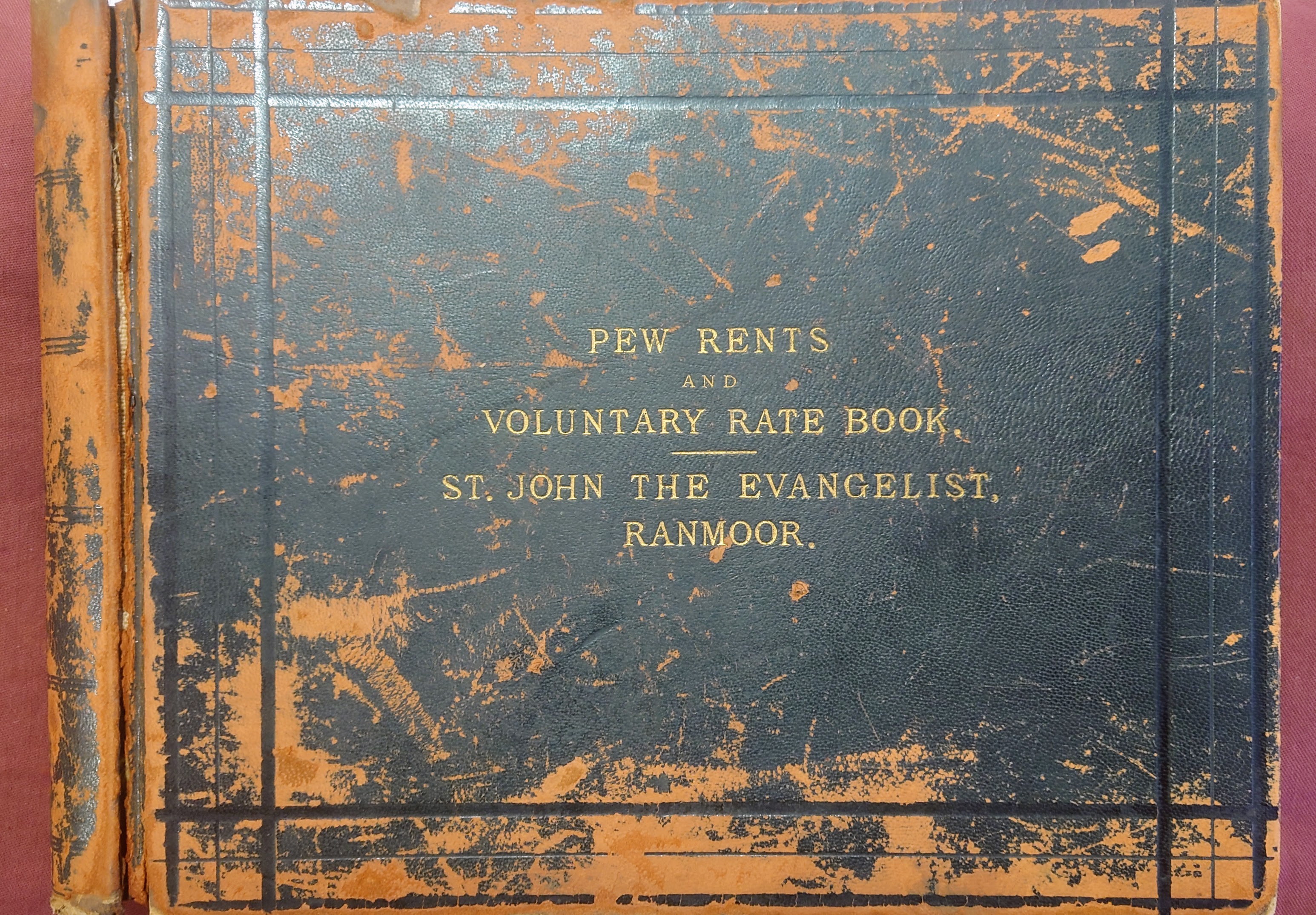

Blog 28: The Man in Pew 62

18th December 2025

Download

If one delves into those who rented pews more closely, there may be a hidden life behind the respectable facade.

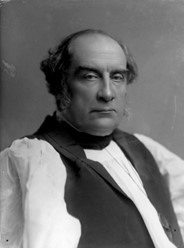

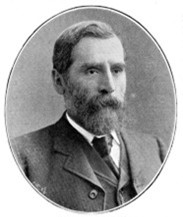

Joseph Bramhall Ellison was occupying Pew 62, 4th from the front, so a prominent person.

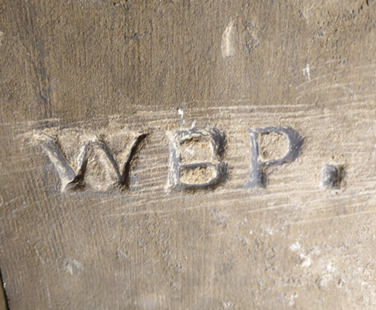

Signage for Kayser, Ellison & Co

He was the son of Joseph Ellison, American representative of Wilson, Hawksworth & Moss, later Wilson, Hawksworth, Ellison & Co. Joseph senior married his wife Eliza or Elizabeth Bramhall in New York, and his two older sons Joseph Bramhall and William Carr were both born in USA. Joseph junior became a steel merchant, having joined his father’s firm with brother William. With a new partner Charles Kayser, in 1860 the company became Kayser Ellison and Co., specialising in steel and wire drawing.

In 1860 he married Helen Thompson, daughter of Robert Thompson of Ranmoor. They married at Fulwood church.

He and his wife were governors of the Deakin Institute for granting annuities to unmarried women and donated regularly - which seems very appropriate as we will see. In the 1891 Census, he was living at 12 Gladstone Rd with his wife and two servants. In 1901 they were at the same address with no children recorded. Helen died on 4th March 1911 but according to the 1911 Census, he appeared to still have a wife! In fact, he had remarried on 15th March 1911 less than two weeks after the death of his first wife, with a special licence, no family as witnesses - just their lodger.

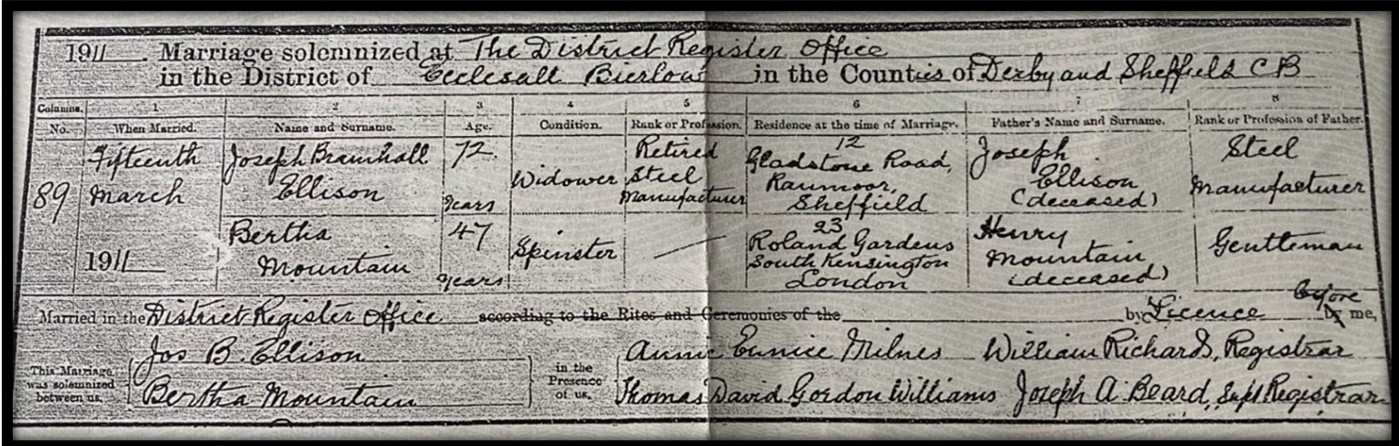

Marriage register entry

The marriage certificate gives the new wife’s name as Bertha Mountain, 47, from Sheffield, though her address is recorded as 23 Roland Gardens, London. Roland Gardens keeps cropping up as we will see. I thought this was quick. But I was even more intrigued when I came to his death in 1913. Joseph was buried in Brompton Cemetery, London – the home address is 23 Roland Gardens, again.

Joseph was recorded on the Electoral Registers as living there as early 1901, so it had been in his possession for a while. It was possible to have more than one vote prior to 1948.

The newspaper account of his funeral surprised me – it named those attending the funeral including two people I had not come across before: Joseph Bramhall and Peter Bramhall Ellison - his sons! What was also odd was that his nephew, the son of his brother William, was also there – another Joseph Bramhall Ellison. It struck me as odd that the two brothers each used the same names for their sons.

I was intrigued so tried to track down these two sons – and found them in the 1901 Census in Bexhill on Sea, aged two and under one.

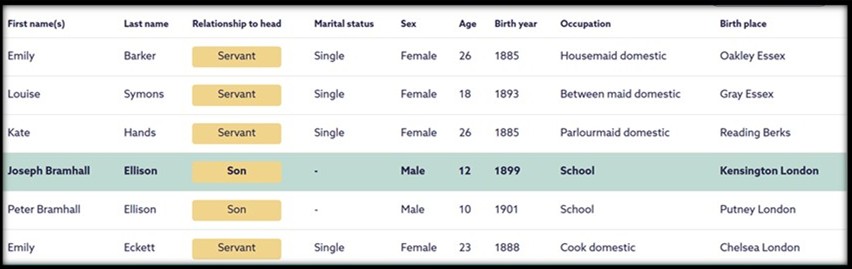

1901 census

Here was a Bertha Ellison, apparently married and living on her own means whose birthplace is Sheffield. Her two sons are living with her plus four servants! The two boys were born in Kensington and Wandsworth. They were both baptised at St Margaret’s Westminster in 1901.

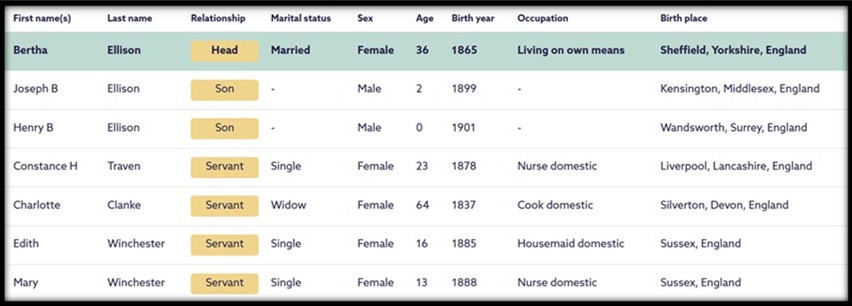

In the 1911 Census, as we have seen, Bertha and her husband Joseph were in Sheffield but where were the two boys? I discovered them in the 1911 Census living at 23 Roland Gardens, Kensington with 4 servants, but no parents. The cook completed the census return.

It seems unlikely that these are not his sons. Perhaps he was keen to have sons to inherit to carry on the family name and the business which was not unusual at the time. Or perhaps he was having a mid-life crisis when he met Bertha - she was twenty-five years his junior after all! But the sons didn’t go into the business. Joseph studied medicine and the younger son went into the navy and ended up a commander with a DSO.

The younger son is also a bit mysterious – in the 1911 census and the report of his father’s funeral. He was named as Peter but I can find no other evidence of a Peter. There is a Henry Bramhall Ellison, with the same birth year and birth place as we can see in his baptism record and in all the census records - apart from 1911.

1902 census

The will of Bertha’s second husband gives us a clue. In 1917 she married Edward Alvey Jennings, a barrister. In the 1921 Census the couple were living at 23 Roland Gardens with his stepson Joseph while Henry is in the navy. In Edward’s will (he died in 1932) he urged her to give to each of her two sons “Bobbie” & “Peter” with his love, £500 each. Perhaps the inverted commas (his, not mine) indicate that these were nicknames – designed to disguise who they were when they were young and which stuck. There is another mention of these names in the Brighton Gazette of January 1905 which had regular listings of visitors to the various hotels and boarding houses. In the Harrisons Hotel there was a Mrs J. Bramhall Ellison, a Mr Henry Booth and Masters Bobbie and Peter Ellison. I am intrigued as to who Henry Booth was, of course!

It is fascinating that Joseph Bramhall Ellison, a pillar of the church community, should be leading a double life with a secret family. One wonders what the rest of the family thought when the two boys appeared at their father’s funeral.

Sue Roe

12 December 2025

Blog 27: The Mansions of Ranmoor

A virtual walk to discover who lived in some of the latgest properties in Ranmoor

23/10/2025

Download the PDF

Choosing which mansions to include in a virtual walk is challenging in the Ranmoor setting because there are so many of the large properties in the area. My choices were made in the end on a kinship theme, with other large houses included because we would have ‘walked past’ them. Many of these family dwellings were later converted into nurses’ homes or halls of residence for the University of Sheffield. They have each had a number of owners so I have highlighted just a few for each of the properties.

The map below shows the route we’ll be taking.

Map: maps.nls.uk

The starting point was Tapton Hall, a mansion that replaced the earlier Tapton Grove that had been built on the site in 1788 by Joseph Badger. This early mansion had also been occupied in the early 19th century by William Shore and his wife Mary, who were the grandparents of Florence Nightingale. The later property was designed by Flockton, Lee & Abbott and built for Edward Vickers in 1854. It was later owned and occupied by the Wilson family (of snuff mill fame) from 1867 – 1958 when it was subsequently purchased by the Freemasons.

Tapton Court

Tapton Court

Tapton Court, an Italianate mansion was built in 1868 for John Henry Andrew who sold the property to Henry Steel in 1879. Steel is a fascinating character – a self-made man who made his money on the race courses of England and became a friend of Edward Prince of Wales, subsequently Edward VII, and of course the founder of Steel, Peech and Tozer, a successful steelmaking business. The house was purchased in 1933 by the J. G. Graves Charitable Trust and became a Nurses’ home until the closure of the Royal Hospital in 1978. It was then a Hall of Residence for the students of the University of Sheffield. A fire in 2010 damaged the building and it remained in a derelict condition until it was purchased and redeveloped in 2020. It has now been converted into 37 new homes.

Walking down the hill we come across Tapton Cliffe – on the corner of Shore Lane and Fulwood Road. This was built in 1864 for John Yeomans Cowlishaw, nephew of John Newton Mappin the brewer, who had moved into Birchlands, just along the road, by 1861. Yeomans was a very talented man, trained as a pearl cutter by Mappin, and his specialism was fruit knives. He also shared his uncle’s passion for art. A later resident of the house, Frank Atkin of Atkin Brothers (Silversmiths) Ltd sold the property for half its market value to the University of Sheffield to be used as a Hall of Residence for female students. It has recently been converted back into a single dwelling.

Tapton Cliffe

Tapton Cliffe

Tapton Edge, on the opposite side of the road from Tapton Cliffe, was built for Edward Firth, the younger brother of Mark. It was designed by Flockton & Abbott in 1864. Its grounds were designed by Robert Marnock (he designed the gardens of many of the Ranmoor mansions). After Firth’s death the house was purchased by William Tozer, partner of Henry Steel, who was involved in the manufacturing side of the business. Tapton Edge was then converted into a nurses’ home for the Royal Hospital in Division Street until 1972 and subsequently into a privately run home for elderly people. It is currently awaiting redevelopment.

Oakbrook is probably the second most famous of the Ranmoor mansions, after Endcliffe Hall. It was designed by William Flockton & Son and built for Mark Firth, of Thomas Firth & Sons. The property was extended in 1874-5, in time for the visit from the Prince and Princess of Wales to Sheffield – they stayed with the Firths at Oakbrook. Firth was a great philanthropist and benefactor for the people of Sheffield. He was a staunch Methodist, funding the building of the Methodist New Connexion Chapel (designed by Flockton) in Broomhill He was also a firm believer in the value of education, serving as the first vice-chairman of the Sheffield School Board in 1870, and by 1879 he had provided more than £25,000 towards the creation of what became Firth College in Leopold Street. It would be interesting to know what his views would have been about his house being used as a Roman Catholic school!

One of the advantages of doing a virtual walk is that the distance between the properties does not matter. The next house on the walk is Riverdale, which is some distance from Oakbrook. This house was built for Charles Henry Firth, the youngest brother of Mark and Edward. The 1898 sales brochure stated that the property had been “erected regardless of cost” and Pevsner describes the house as “sumptuous Gothic”. Firth and his second wife Marianne (née King) were Anglicans, and great benefactors to St John’s church. In 1881 Firth became managing director of Thomas Firth & Sons after the death of his eldest brother Mark. The house was then bought by J. G. Graves, who by 1903 employed more than 2000 people in his mail order business. The property has now been converted into apartments.

Tapton Grange is the only mansion on the “walk” that no longer exists. It was built on a three acre site for James William Harrison, who remained unmarried. The grounds were designed by Marnock. Harrison was in partnership with his brother Henry and friend William Howson who took over Thomas Sansom & Sons and rebranded it to Harrison Brothers & Howson. Henry Harrison moved to America; Howson was the Traveller and James Harrison remained in Sheffield. During his lifetime he was a great benefactor to local hospitals and schools and provided the land on which St John’s Ranmoor was built. Later owners include the National Union Teachers’ Benevolent Fund which used the house to provide a home for teachers’ orphans. It was demolished in around 1970 and the site was split into two. The northern part provided the land for the Ballard Hall of residence for the then Sheffield Polytechnic; the southern part was developed as Oakbrook View, which included a hostel for the council’s Social Services Dept. Both of these developments were demolished some time ago and the land has now been redeveloped for private residences.

Tapton Grange

Tapton Grange

Tapton Park Road was created in 1863 by the trustees of the Boys’ Charity school. Moordale was built on land at the junction of Tapton Park Road and Fulwood Road, and purchased by James Nicholson. The house was probably designed by Hill & Swann. Nicholson worked with his brothers William and John in John Nicholson & Sons, cutlery manufacturers in Mowbray Street. The firm had been established by their father. James Nicholson moved to 7 Broomfield Road in around 1873 after the death of his first wife, Harriet. After being converted into offices for various companies the property became the Fulwood Inn in 1999, now known as The Florentine.

The property named Tapton Park was built in a two acre site on the north side of Tapton Park Road. It was owned by William Howson, business partner of James Harrison who lived on the south side of the road. Howson devoted himself to the business until his death in 1884. His son George also worked for Harrison Brothers and Howson but was more active outside the company, becoming Master Cutler in 1893. The property remained in family hands until 1936 when it became the head office of General Refractories. It is now known as Tapton Park House and is private residences.

Our final mansion on the walk is Thornbury, built in 1865 for Frederick Thorpe Mappin, the eldest son of Joseph Mappin and his wife Mary (née Thorpe). After the death of his father Frederick took over the family business (Joseph Mappin & Son) and looked after his three younger brothers (Edward, Joseph Charles and John Newton (the younger)). Frederick had married Mary Crossley Wilson in 1845, daughter of John Wilson a cutler, who lived at Oakholme. When John Newton (the younger) became a partner in the family firm in 1857 disputes arose and the firm was dissolved. Frederick became the senior partner in Thomas Turton & Sons; Edward & Joseph formed the partnership Mappin Brothers and John Newton moved to London, met and married Ellen Elizabeth Webb in 1860 and went into partnership with her brother George Webb jun. and they traded as Mappin & Webb in a partnership that flourished.

Frederick & Mary’s middle son Wilson Mappin married Emily Kingsford Wilson in 1876, daughter of George Wilson of Tapton Hall. Frederick Mappin continued to progress both locally and nationally. He became a town magistrate in 1870, Town Trustee from 1871 and became Mayor in 1877. He was elected to parliament in 1880, representing East Retford and later was Liberal MP for the Hallamshire Division of the West Riding of Yorkshire from 1885-1905 after his original parliamentary seat was abolished. He became a Pro-Chancellor for the new University of Sheffield in 1905 and the Faculty of Engineering is now housed in the Sir Frederick Mappin Building, in Mappin Street, renamed in his honour. He died in 1910 and Thornbury was then occupied by Wilson & Emily Mappin. Wilson died in 1925; Emily died in 1940. After her death the house became an annexe for the Children’s Hospital until in 1991 when it reopened as a private hospital.

So, we have now come full circle. All the properties started as mansions for the steel magnates of the mid-19th century and all but one still exist, albeit rarely in the same format as a single residence:

• Tapton Hall – Masonic Lodge

• Tapton Court - residential apartments

• Tapton Cliffe - being developed into a single residential property

• Tapton Edge -awaiting development

• Oakbrook – Notre Dame School

• Riverdale – private apartments, with other apartments in the grounds

• Tapton Grange – demolished and the land developed for housing

• Moordale – The Florentine

• Tapton Park – residential

• Thornbury -private hospital

This is of course just one walk of many possible strolls around the suburb of Ranmoor which is rich in such properties.

Judith Pitchforth

20 October 2025

Blog 26: A Walk Down Ranmoor Market

Part Two: Ranmoor’s Shops, People and Public Houses

01/10/2025

Download the PDF

This week’s blog is the second instalment of our two-part commentary that accompanied our summer walking tours ‘A Walk Down Ranmoor Market’. This part focusses on Ranmoor’s shops, people and public houses.

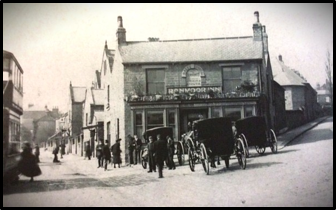

This image, probably from around the late 1890s, shows us the Bull’s Head occupied two of what must have been originally a short terrace of three cottages. This reflects the pub’s origins as a private house. Records show that around the mid-nineteenth century, pen and pocketknife manufacturer Jonathan Swann lived here with his family and that they added to their income by selling beer. However, it seems that the next occupants, took the business on as an established public house. This was Charles Slowe (1866 - 1880s) and his family. Charles had married his wife Catherine at St John’s, and their daughter would go on do so too. It was also Charles who changed the name of the establishment to the Bulls’ Head.

Returning to the photograph, it may be possible to make out A.B. SLOWE above the door. This was Albert Benjamin Slowe, who took on the proprietorship of the pub from his father in 1885. Albert advertised his establishment as ‘a First-class Old-Established Country Inn, situated … amidst the most charming scenery that Sheffield possesses ...[with] Cabs, Billiards, and Cricket Ground attached’.

The western third of the building remained as a cottage until around 1900 and we can see that there’s a wall dividing the front garden from the pub’s front yard and a man is leaning in his doorway. He’s mirrored by the two people outside the pub – one with a bowler and moustache posing with one foot on the doorstep while the other looks like a youngster, standing with his thumbs in his waistcoat pockets. Marr Terrace is just visible on the right.

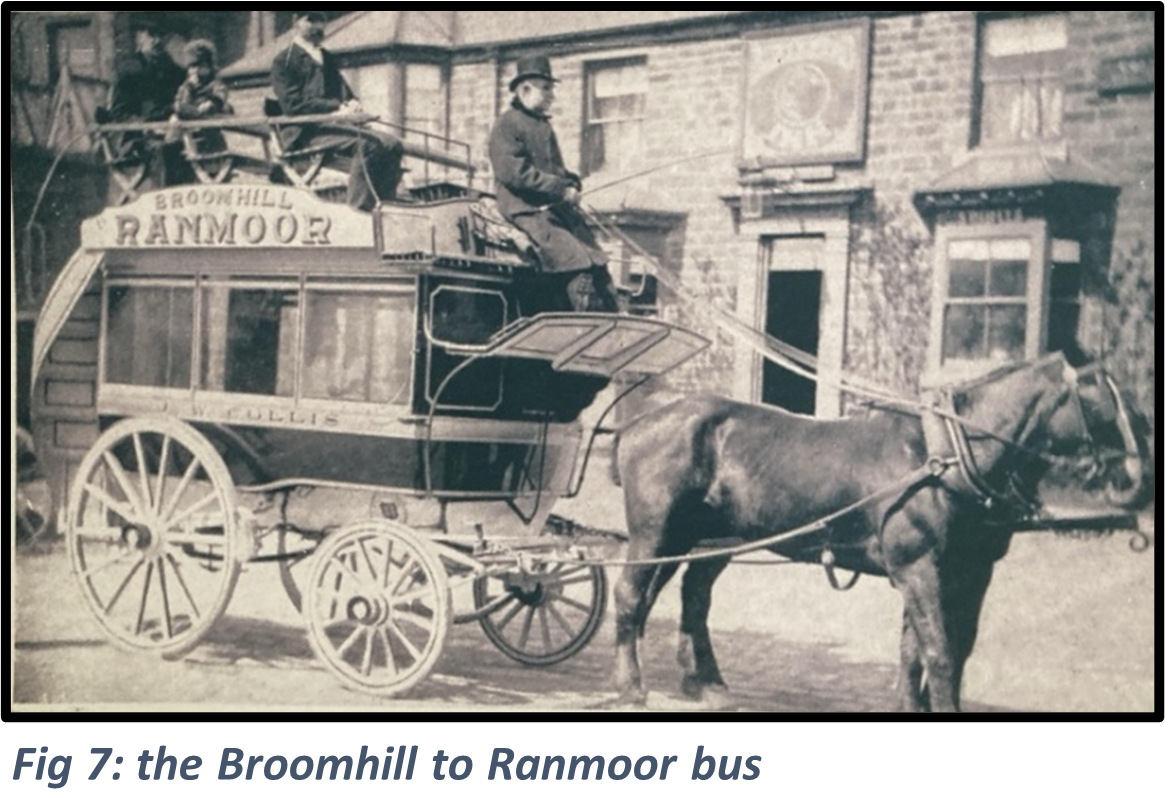

There’s a sign for COLLIS’ CAB STAND next to the window on the right of the pub and figures 7 and 8 illustrate how the Bull’s Head served as a transport hub between the 1850s and early 1900s.

This service ran between the Bull’s Head at Ranmoor Market and the York Hotel in Broomhill – a journey of about a mile. Look closely and you will see on top a little boy standing clutching the rail. His name was Joseph Cyril Lockwood and he later recognised himself in this picture when it was included in a book published in the 1940s.

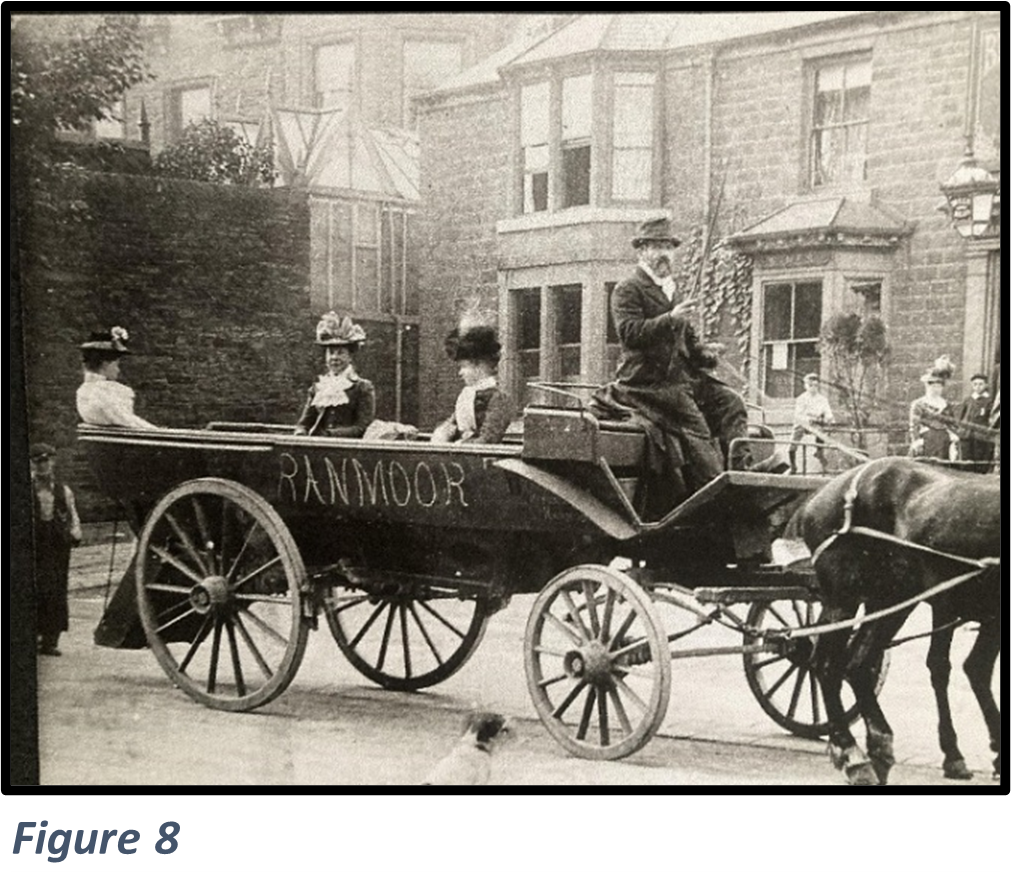

Figure 8 shows the driver posing, (perhaps a little begrudgingly), with his whip raised. The stance of the horse’s rear legs suggest it is resting; maybe the horse and driver had been in that position for some time while the photographer was setting up his shot. The ladies in the carriage look as if they’re dressed up for the occasion, as do the onlookers standing by the pub entrance. A boy is standing to the rear their carriage, looking as if he’s enjoying the scene, as does the little dog in the centre foreground. Perhaps this picture was taken at the start of a special holiday outing.

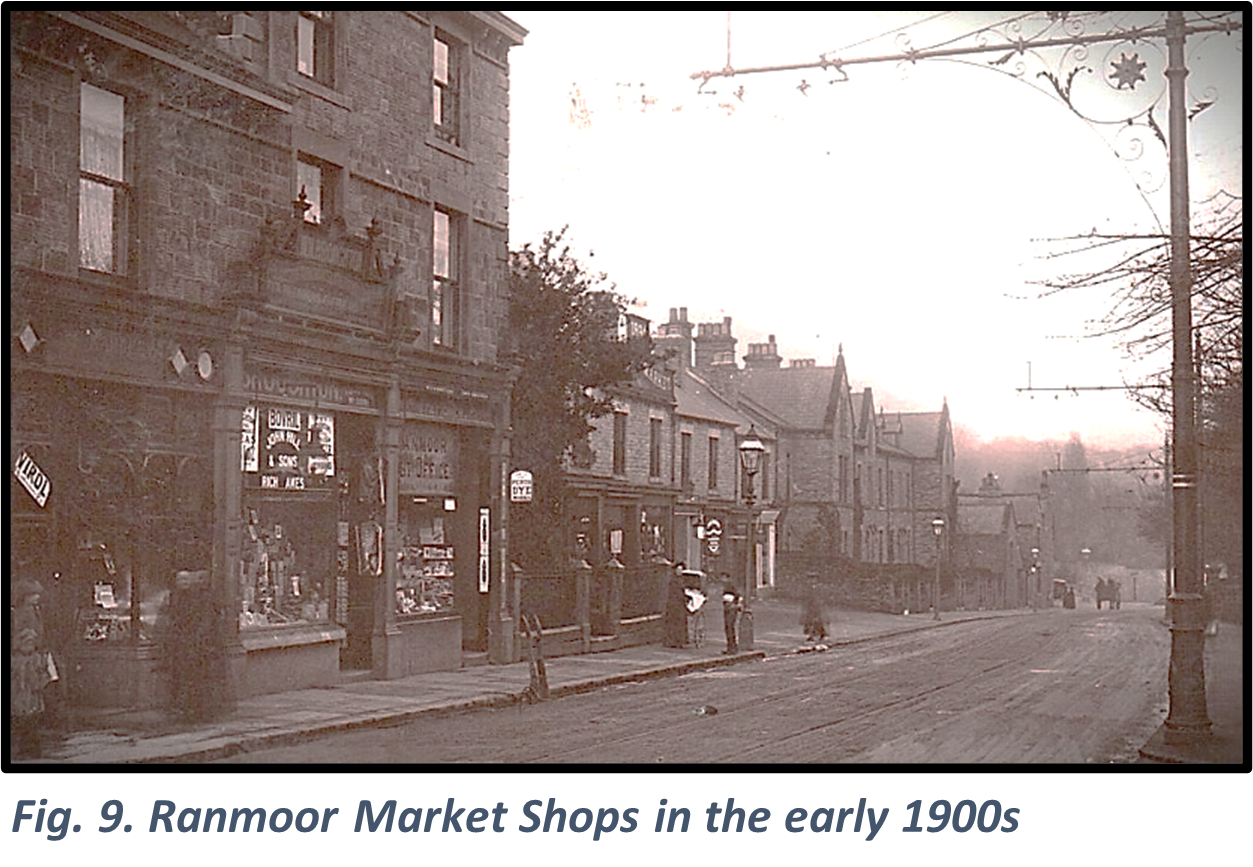

The photograph in figure 9 was probably taken around the same time, (perhaps the same day), as figures 4 and 5 with the same tramlines and overhead cable supports visible and the same bare wintery branches from overhanging trees. Nearest to the camera is a row of three shops which provide fine examples of Victorian shopfront design. Their beautiful window displays are crammed with enticing goods. These buildings retain their traditional features to this day and are best viewed from across the road. From this distance, you can appreciate how the carved stone pilasters with their floral details provide a balanced frame for the shopfronts.

On the left edge of the photo is Eardley’s Chemist, perhaps the most elegant of the three. An advert for VIROL stands out. Virol was developed by the makers of Bovril in 1899 and was a popular food supplement during the early 20th century, promoted with the slogan ‘Children Thrive on Virol’. On the fascia above the chemist’s window there are three pale shapes - two diamonds and a circle. Still visible today, these shapes contain the date 1879 and what may be images of apothecaries.

In the middle is Broughton’s Grocers: ‘Provision Merchants and Italian Warehousemen’. ‘BOVRIL’ and ‘PICK AXES’ are advertised and a wooden hand truck is propped up against the kerb.

The final shop of the trio, (furthest away from us in the picture), is the Post Office. There is a sign for DYE attached at right angles to the end column. Prior to this, it had been one of the outlets for Ranmoor’s Wildgoose brothers who were the original owners of these shops and who sold meat, fish, game and poultry. This end unit became a Post Office and stationers in the early 1890s.

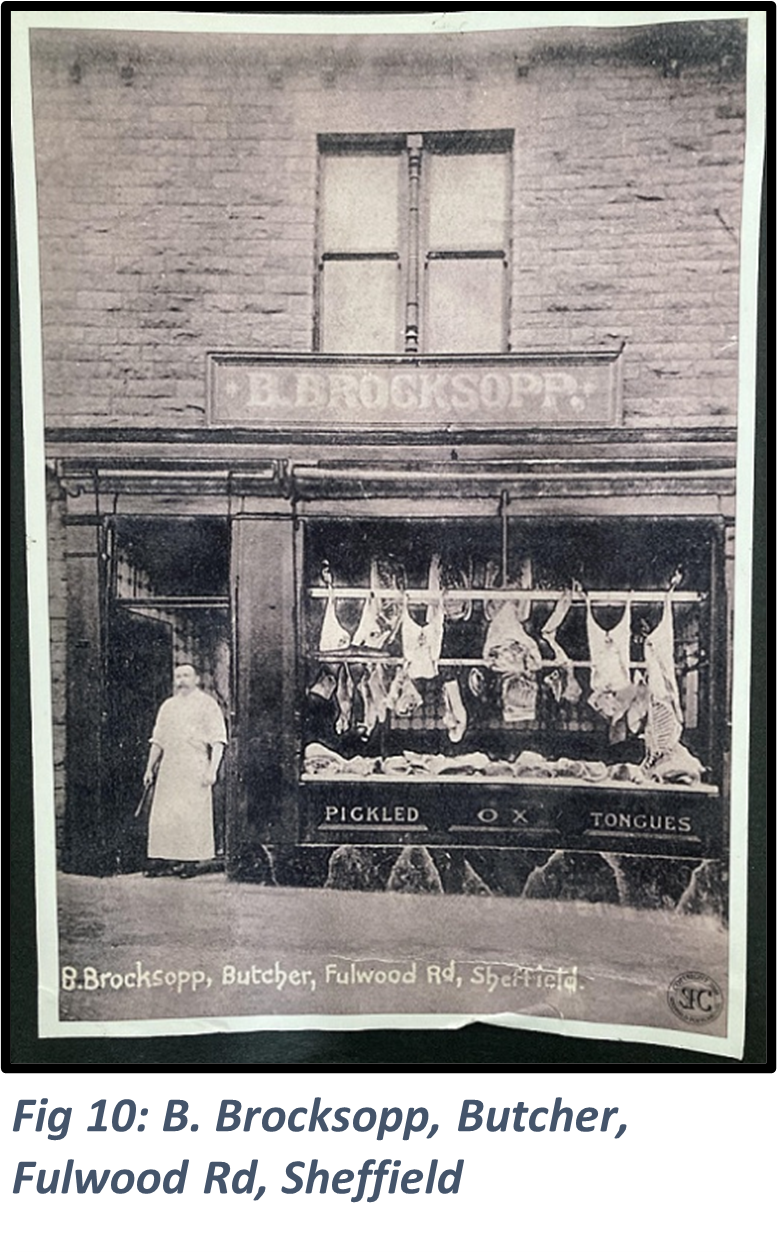

We saw Brocksopp’s butchers earlier in figure 5. This time we see Arthur Benjamin Brocksopp (1867-c.1945) standing in the doorway. Benjamin Brocksopp and his family, (which included his wife Susannah and six children), lived here above their shop from 1895-1936. Brocksopp was from a family of butchers based in Broomhill who moved west to set up business in the new Ranmoor Market. Brocksopp’s was the first in a long line of butchers trading from number 370 Fulwood Road, continuing with Chris Beech, whose name now stands above the shop window. The steel runners for hanging the meat carcasses seen in the photo are still in situ. The Brocksopp family grave is in Fulwood Churchyard.

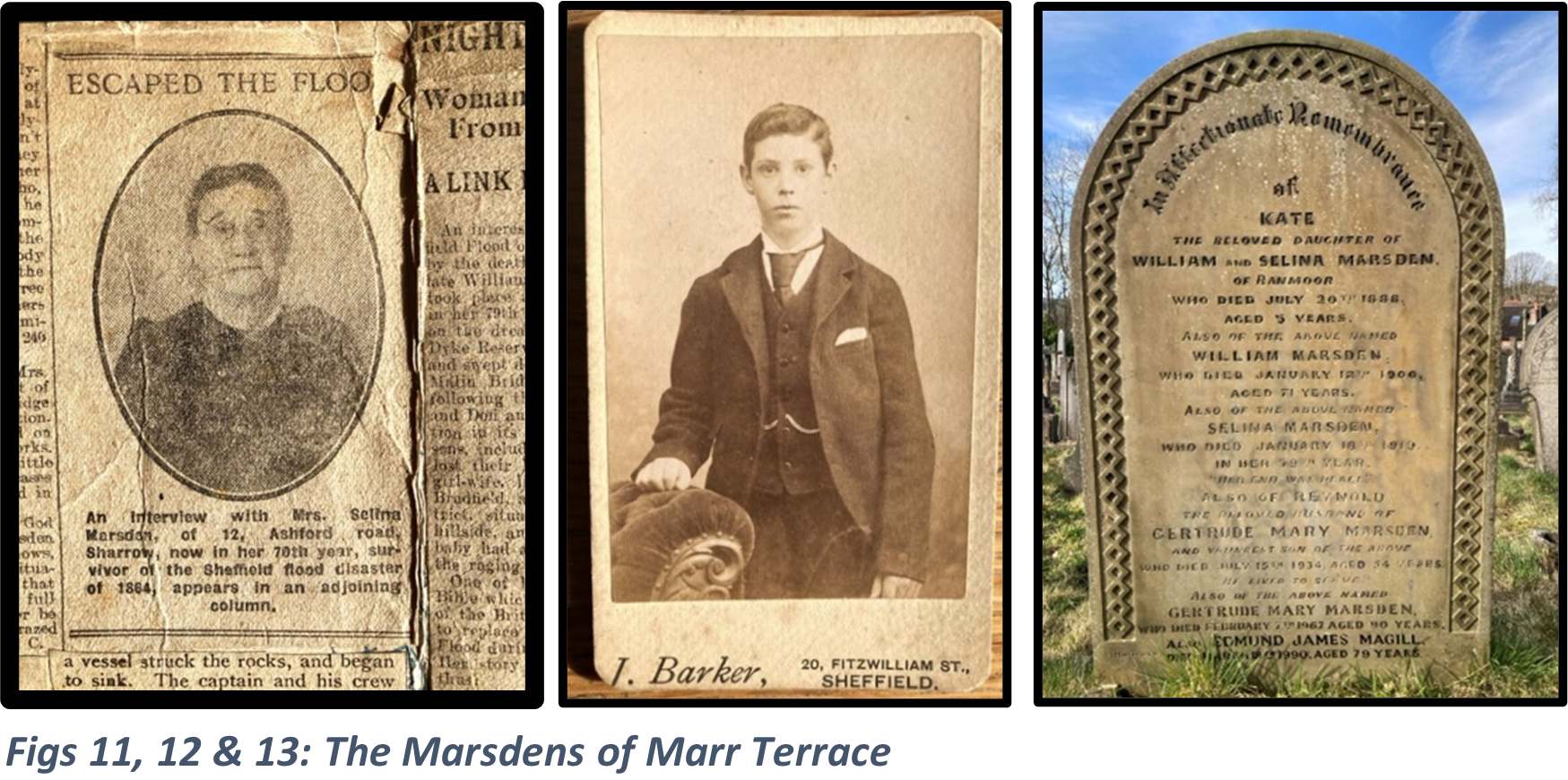

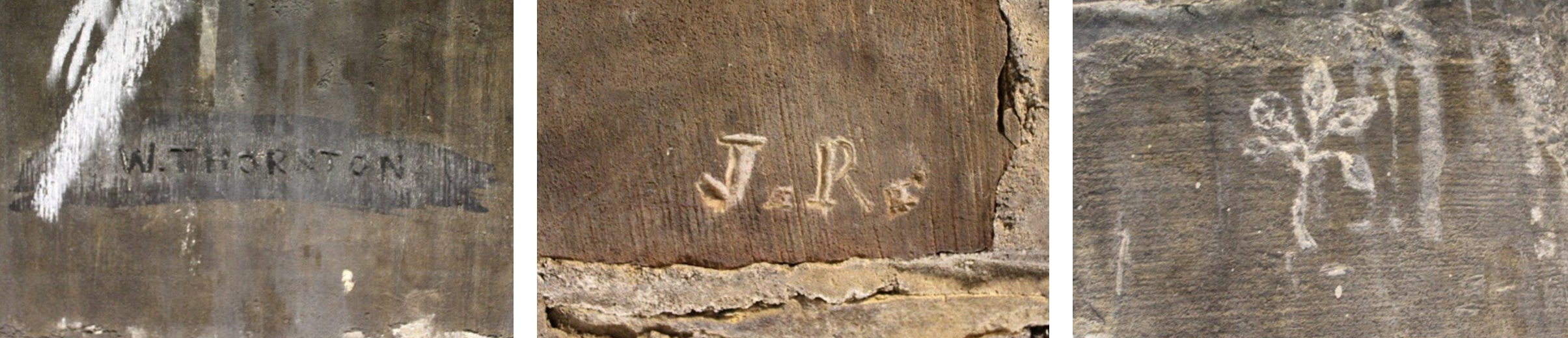

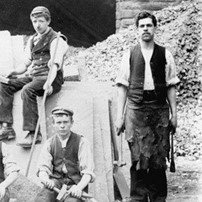

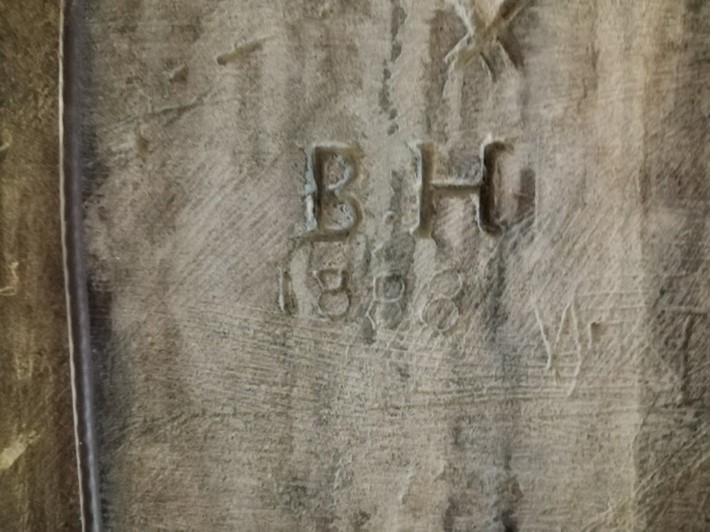

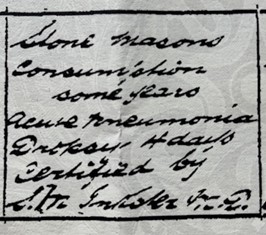

These images relate to the Marsden family of Marr Terrace. The Marsdens are a family with roots and branches across the old Upper Hallam area. Several Marsden families lived on the sloping terraced street which was originally called ‘Market Place’. Selina and William Marsden raised their family of nine children right at the top of Market Place at number 41 between 1880s and the 1900s. William was a stone mason, perhaps employed in the construction of St. John’s Church, and all five of his sons would go on to follow their father’s trade. In 1864 Selina (aged 23), William (aged 37) and their two-year-old son John were living on the edge of Dale Dyke Dam when it burst. The newspaper article on the left is from an interview with Selina, (aged 70 in the photograph), where she recounts their terrifying and brave escape from the flood waters some fifty years previously. Their youngest son Reynald (1879 – 1934) is pictured as he begins his adult life aged 14, when he was living at Marr Terrace. To the right of Reynald is a picture of the family gravestone in Fulwood Churchyard. The inscription at the top remembers Selina and William’s youngest child, Kate, who died aged just five.

Fig 14: map 1875 Fig 15: Early 1900s showing two forms of transport

The Ranmoor Inn: the final stop

Our tour of Ranmoor Market concluded with a look at the Ranmoor Inn. Facing east towards town and welcoming travellers passing along the road to Fulwood, the story of the Ranmoor Inn mirrors that of its west end-counterpart, the Bull’s Head. It started as a ‘beerhouse’ in the 1850s, principally run by Sarah Worrall whose husband James was a bootmaker. After the death of Sarah and James in the 1860s, their son George took over, transforming their private house into a public house, licensed to sell alcohol and looking like the building we see today.

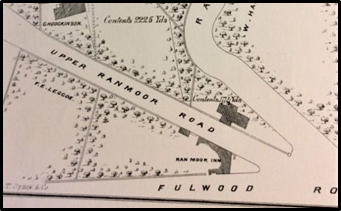

This sale plan shows how the pub stood almost alone on its spur of land in 1875. There is the distinctive shape of a church across the road - Ranmoor St. John’s was built on this site four years later.

The image above suggests the hustle and bustle around the inn in the early 1900s and captures a time of transition in transport. To the left, a woman is stepping onto a tram while the centre of the photograph is dominated by horse-drawn cabs waiting for fares.

Our look at Ranmoor Market concludes with a quieter scene from the early 1900s. The Ranmoor Inn has a flagpole, while the arched sign reads GOOD STABLING and RAOB. The letters stand for Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes which was a philanthropic organisation for men and their families.

Set into the floor outside the pub, this old iron ring was used to lower beer casks into the cellar.

Conclusion

The guided walk on which this piece is based invited us to ‘meet’ past residents of Ranmoor Market. As well as looking back to historical records for information, I also sought the perspectives of the present Ranmoor shops community which included current residents, traders and their living descendants. Their contributions brought life and warmth to the project and highlighted the threads connecting the past to the present. I am very grateful for their help with my research.

Jane Bartholomew

21 September 2025

Bibliography

Doe, V. (1976). Some Developments in Middle Class Housing in Sheffield 1830-1875. Pollard, S. & Holmes, C. (eds.) 1976. Essays in the Economic and Social History of South Yorkshire. South Yorkshire County Council. 174-186.

National Library of Scotland: https://maps.nls.uk/

The Ranmoor Society: https://ranmoorsociety.uk/

Reid, C. (1976). Middle Class Values and Working Class Culture in Nineteenth Century Sheffield – The Pursuit of Respectability. S. Pollard and C. Holmes (eds.) 1976. Essays in the Economic and Social History of South Yorkshire 1976. South Yorkshire County Council. 275-295.

Warr, P. (2009). The Growth of Ranmoor, Hangingwater and Nether Green. Northend.

Blog 25: A Walk Down Ranmoor Market

17th September 2025

Download the PDF

Introduction

‘Ranmoor Shops’ is a familiar geographical reference point for many of us who live locally but if we were to say we were going to ‘Ranmoor Market’, we might be met with blank expressions. Yet this was the name given to Ranmoor’s collection of shops over the later Victorian period. As someone with an interest in local history, I was curious to find out more about this short stretch of Fulwood Road: who lived and worked here during this later Victorian and early Edwardian period? Through my research, a picture the community emerged, providing an insight into Ranmoor society during a period when this rural and somewhat remote part of Upper Hallam was becoming an upmarket suburb.

It became apparent that Ranmoor Market would be an ideal focus for guided walks as part of the Scissors Paper Stone Community History Project. The following is a two-part commentary on the images used in a booklet to accompany these walks and presents a selection of the material that was covered.

Part One: background and overview of Ranmoor Market

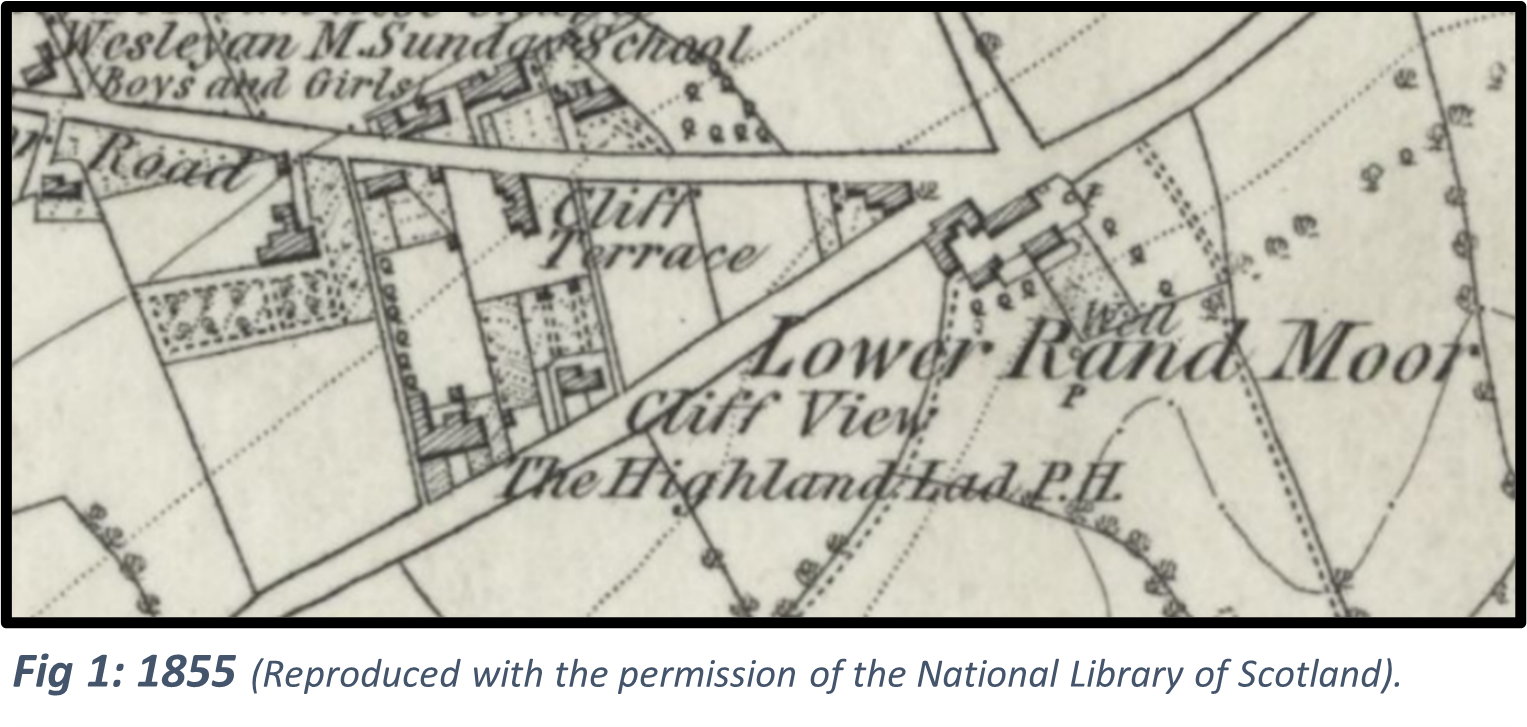

The following three maps give an indication of how the area developed through the Victorian and Edwardian periods.

This map tells us that we are looking at Lower Rand Moor. ‘Rand’ is derived from an Old English word meaning ‘brink, bank’ or ‘edge’ so the place name may reflect the once open landscape which included some sort of edge or cliff. Just above the word ‘Rand’ you will see what are probably farm buildings, a well, fields and orchards. These belonged to Joseph Ibbotson, who also rented a grinding wheel on what is now known as Ibbotson’s Dam in Bingham Park. The building across the road which nestles into the point of a triangle of land will soon become known as the Ranmoor Inn. However, it’s not recorded as a public house on this map. Looking to the left of this, you will see the words Cliff View and Cliff Terrace. Judging by local place names, the ‘cliff’ was clearly a significant feature of the landscape in Victorian Ranmoor. Cliff View, (now the West 10 Wine Bar), was the house and grocer’s shop belonging to local farmer Isaac Deakin (1789-1859). Cliff Terrace was to be renamed Deakins Walk in the early twentieth century, (losing its apostrophe somewhere along the way), to recognise Deakin’s significance to the area. Not only was Deakin a pillar of the community but he was also very likely Ranmoor’s first shopkeeper, setting up his business here in the 1840s.

Left of Cliff View it reads The Highland Lad P.H., indicating that this former ‘beerhouse’ has already become established as a pub. It will soon be known as The Bull’s Head. Moving clockwise to the top left of the map, you will see the words Wesleyan M. Sunday School Boys and Girls. This would have been the local school for many of the children living in the Ranmoor Market area.

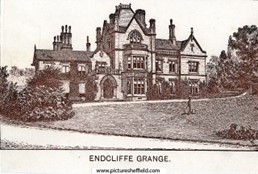

This map reflects the impact of Sheffield’s industrial revolution on this little rural area. During the second half of the nineteenth century, owners of Sheffield’s businesses and factories were drawn towards areas such as Ranmoor to escape the pollution and crowding of the town. Perhaps the most notable pioneers of this westerly migration were Sir John Brown of Endcliffe Hall and Mark Firth of Oak Brook. They were followed by other wealthy families who lived in the villa-residences built during the later Victorian and early Edwardian periods. An example is Rockmount which can be seen to the immediate left of the Bull’s Head (both circled), towards the bottom middle of the map. In addition, existing buildings such as the Ranmoor Inn, (in its triangle over to the right), have been developed and roads have appeared. In particular, the straight block of Marr Terrace is now visible above and to the right of the Bull’s Head, running between Fulwood and Ranmoor Roads. This narrow street of red-brick terraces was built in the 1870s partly with the intention of appealing to people who might be employed as domestic servants in the area. Census returns tell us that a significant proportion of gardeners, grooms and coachmen lived on Marr Terrace during the late nineteenth century.

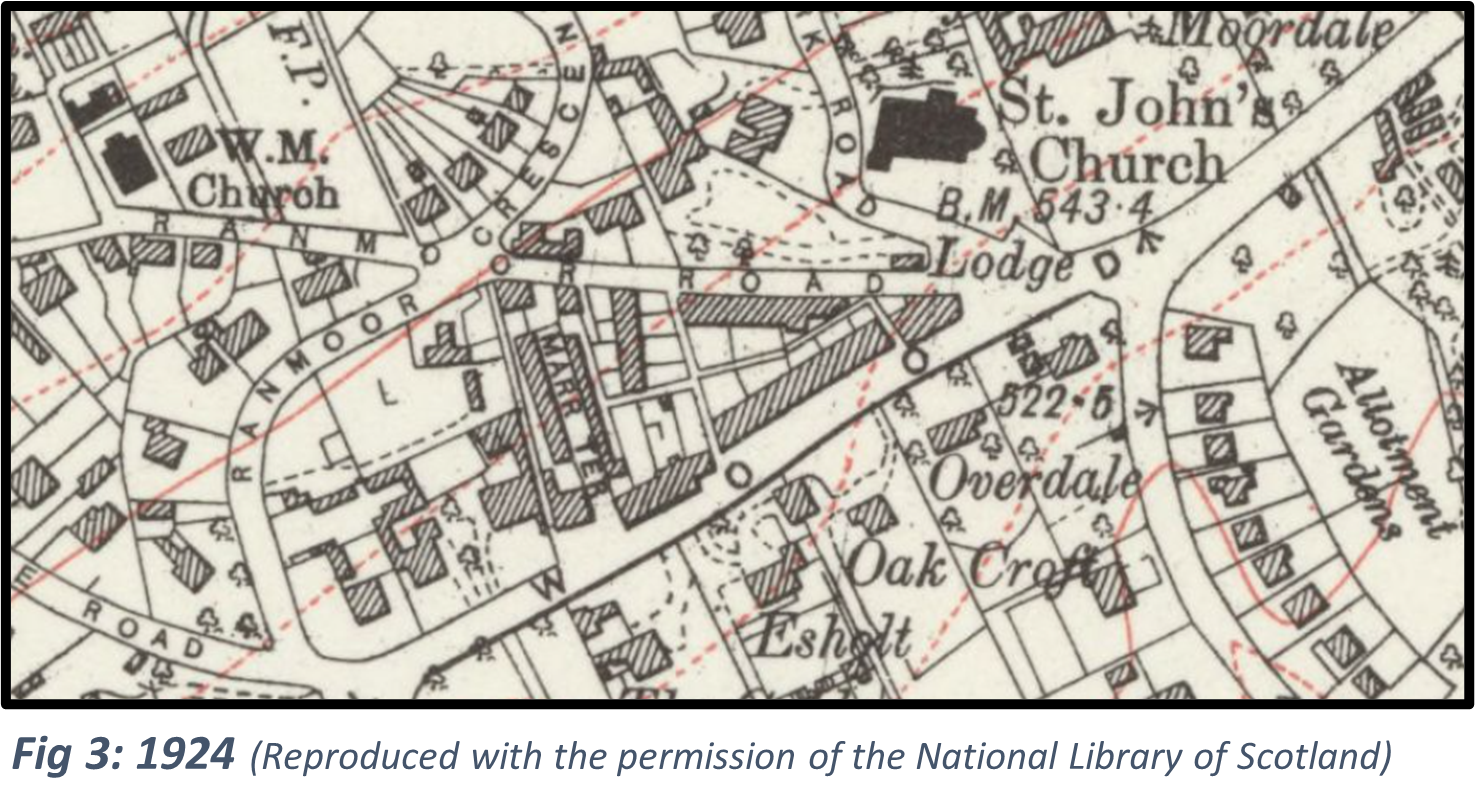

This shows us that by the early twentieth century, the area had grown to closely resemble what it looks like today. The trio of Overdale, Oak Croft and Esholt are now visible. These are examples of ‘that architectural curiosity – the Victorian villa- residence’ and domestic servants were employed in all three throughout our focus period. Another impressive house from this era, Moordale, is just discernible in the top right of the map. St John’s Church, out of the area of the previous map, has a strong presence and the former Sunday School for Boys and Girls is referred to simply as W. M. Church. Most local children would now be attending the Ranmoor Council School, (now Nether Green Junior School), which opened in the early 1900s. Marr Terrace is marked on this map with the letters MARR TER.

Fig. 4: The west end of Ranmoor Market

Ranmoor Market at street level

The tram tracks and ornamented posts for overhead cables tell us that the following photographs must have been taken at some point after 1901when tram routes reached Ranmoor. However, both images show how horse-drawn transport was still the norm, as was the use of shop awnings.

Fig. 5: The east end of Ranmoor Market

The edge of the Bull’s Head and entrance to Marr Terrace can be seen to the left of this photograph, followed by the first phase of shops which were built from around the 1850s to the 1880s. The spire of Ranmoor St. John’s can be made out behind the chimneys.

This image shows the set of shops running towards the Ranmoor Inn with the spire of St. John’s standing tall in the background. These were built towards the end of the nineteenth century. ‘B. BROCKSOPP’ stands out in pale lettering above the display window with ‘PICKLED OX TONGUES’ advertised below. This is Benjamin Brocksopp’s butcher’s shop from which he traded over the period 1895 to 1936. Just below the centre of the picture, a woman can be seen sweeping the pavement – presumably she worked at one of the shops. A man in a cap is driving a cart east down Fulwood Road. It seems to be carrying a milk churn, probably supplied by one of the many farms in the area. Lining the road between the Market shops and the Ranmoor Inn is the symmetrical residential row of Ranmoor Terrace, (built in the 1870s), with its pinnacles topping the apex of each gable end.

These scenes look strikingly familiar: very little has changed in terms of the streetscape and there is even continuity through the businesses which trade to this day.

After this overview of the Ranmoor Market area, Part 2 will go on to focus on some of its people, shops and pubs.

Jane Bartholomew

14 September 2025

Edwards, A. M. (1981). The design of suburbia: a critical study in environmental history. Pembridge Press.

Blog 24: A Simple Will

2nd September 2025

Download here

On Saturday 13 September, for the Heritage Open Days festival, Sue Roe, Mary Grover and I are giving a talk, ‘The Wills of Ranmoor Residents: Who Gave What to Whom’, based on our research into the lives and legacies of the parishioners who rented pews in 1890. If you want to come along (and we would love to see you), you’ll find the details below.

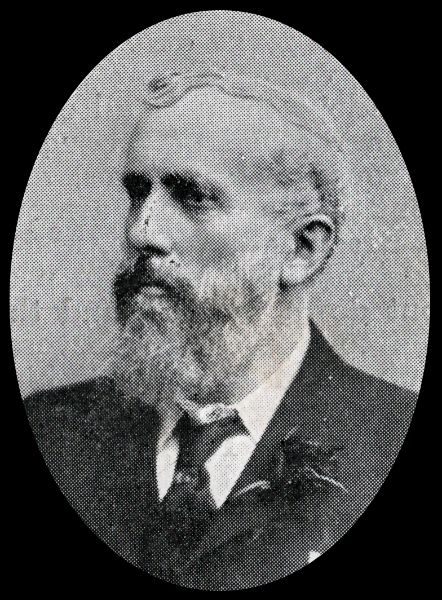

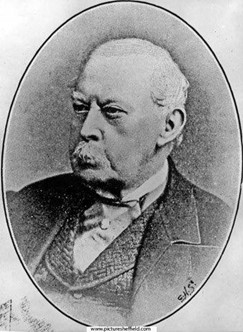

Sir John Bingham (from Picture Sheffield. Ref: y14723).

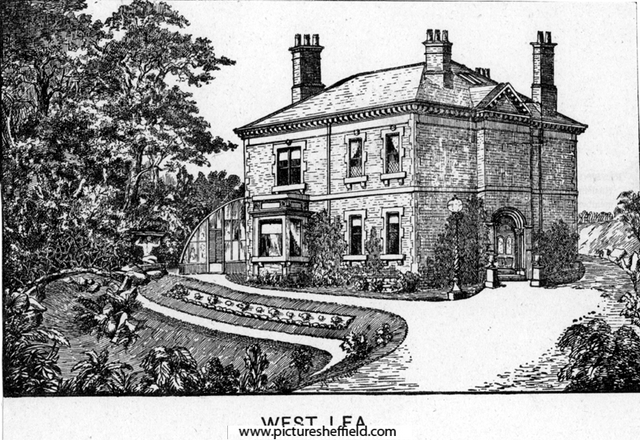

By way of a taster, we are sharing the will of Sir John Bingham of West Lea (which you may know better as St John’s Parish Centre). This is one of the shortest and simplest wills we have but, as you’ll see, we can learn a lot from it, about both the society of Bingham’s time and about wills.

John Bingham was one of Ranmoor’s great industrialists – and a fine example of Victorian self-improvement. Born the son of a grocer in 1838, he became the managing partner of Walker & Hall, the silversmithing business which pioneered electro-plating. He employed thousands of Sheffielders in its works between Eyre and Howard Streets in the city centre and also around the world. Many, if not most, homes in the UK have had Walker & Hall tea and coffee services and cutlery at some time or another. Bingham was Master Cutler twice, in 1881 and 1884, and he was created a baronet in 1884. He is described as a forceful character, Protestant, Conservative, a magistrate and a volunteer delighted to be Honorary Colonel of the West Yorkshire Engineers. The Sheffield Independent (19 March 1915) remarked in his obituary:

West Lea around 1885 (Picture Sheffield. Ref: s05856).

He was so strong in his convictions that it was only natural that he provoked vigorous opposition. No matter what the subject might be when once he saw the goal he went straight to it, and ever afterwards it was one of the incomprehensible things of life to him why others did not go too.

‘Not altogether a popular man … He strove for causes, not for favour’ and ‘pig-headed’, said the Sheffield Telegraph (19 March 1915) more bluntly but still admiringly. Bingham died suddenly in London in 1915 and was given a grand funeral, escorted the two miles from West Lea to All Saints Ecclesall by thousands of Walker & Hall workers and soldiers. (If you’re wondering why he wasn’t buried at St John’s, it has no room for a graveyard.)

Sir John Bingham’s funeral leaving West Lea and St John’s on 20 March 1915. Notice the gun carriage. (Picture Sheffield. Ref: y05642.)]

Here is Bingham’s will – all 90 words of it:

THIS IS THE LAST WILL of me JOHN EDWARD BINGHAM of Sheffield Baronet I appoint my wife and my son to be EXECUTORS hereof I give to my son all my capital in the business of Walker & Hall and all profits & income accrued & accruing therefrom not already at the time of my decease paid over to me I give to my wife for her life all the residue of my property & subject thereto I give the said residue to my son DATED this 13th May 1910 - JOHN E BINGHAM Signed by the testator in out presence and by us in his the word "therefrom" having first been interlined after the word accrued HEBER WARD GE BRAUM

ON the 7th day of July 1915 Probate of this will was granted to Dame Maria Bingham and Sir Albert Edward Bingham the executors

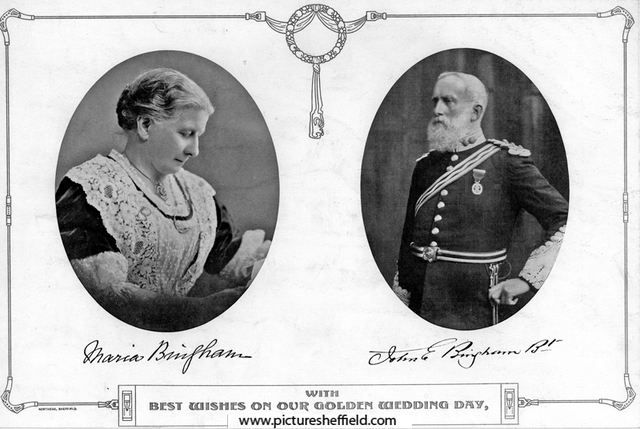

Sir John and Lady Bingham on their Golden Wedding in 1913. Notice Sir John in his military uniform. (Picture Sheffield. Ref: s08977).]

The probate document tells us that the estate was valued at £342,000, over £20 million today, making Bingham one of the richest men in Ranmoor (and therefore all Sheffield). The Nottingham Journal (12 July 1915) commented on his will that he ‘disposed’ of his property ‘at £3,800 per word’.

A will is a good starting point for research. We learn the full names of the family: John Edward, Maria, and Albert Edward. Bingham is a baronet, the lowest rank of the nobility, and his son inherits the title, hence ‘Sir Albert’. The baronetcy would of course have died out if the Binghams had had only a daughter. Official records reveal that Edward is a Bingham family name. Maria is described as ‘Dame’, but she would usually have been known as Lady Bingham.

The will is straightforward. Bingham leaves his business interests to his son and his other property, including West Lea and its contents, to his wife for her lifetime and then to his son. Albert was already a director of Walker & Hall, and it’s a rare Victorian who leaves business interests to a woman, or rather who expects a woman to play a role in business. Widows and daughters inherit shares and then live on the income.

It is notable that Bingham does not leave any bequests to family, friends, servants, institutions or charities. He appears to have been generous in his lifetime, supporting hospitals, his volunteer soldiers and St John’s, to which he made generous annual donations. In 1911 he and his wife gave Bingham Park to the people of the city. He was also, like many Ranmoor men, a Freemason and presumably involved in their charitable activities.

Register of Pew Rents from Sheffield Libraries and Archives.]

This is, by the standards of our Ranmoor collection, a modern will. It’s typed rather than handwritten (which makes life a lot easier for a researcher). Bingham names his wife as an executor at a time when this was still relatively unusual.

The will is dated 1910, five years before Bingham died. We don’t know if he was feeling ill or was just being prudent when he made it. Judging by the witnesses, Heber Ward and G E Braum, it may have been signed at or through his business, rather than the more usual firm of solicitors. Heber Ward was a manager at Walker & Hall, but I can to my frustration find no trace of G E Braum. Perhaps he was just visiting from abroad, as there are very few Braums, and no G E Braum, in British official records or in commercial directories. Of course, ‘G E Braum’ might be a typo (there is another, if you read the will carefully, and you’ll also see that a missing word was added at the last minute). But surely a witness would notice an error in his own name.

That there doesn’t seem to be the hand of a lawyer anywhere is interesting. Whoever drafted the will was aware of the common practice of avoiding ambiguity by avoiding punctuation. There’s not a comma or full stop in the piece. The apparent lack of a lawyer doesn’t of course make the will any less valid - although it may account for its being so short.

Short or long, typed or handwritten, simple or complex, dealing out fortunes or a few pounds, wills are a fascinating way to unlock the history of St John’s and the people who worshipped from its pews.

We will be talking about the Victorian wills of Ranmoor at St John’s Church (Ranmoor Park Road) at 4pm on Saturday 13 September. The talk is free and there’s no need to book. There will be refreshments on sale, and the church is open from 2pm for you to explore.

Val Hewson

1 September 2025

Sources: Wills are available from the Government’s digital wills service. Newspapers are accessed via the British Newspaper Archive and official records via Ancestry.

Blog 23 A Special Occasion at St John’s

22nd July 2025

Download as a PDF

In which a prince, a philanthropist, 40 constables and a large dog go to church…

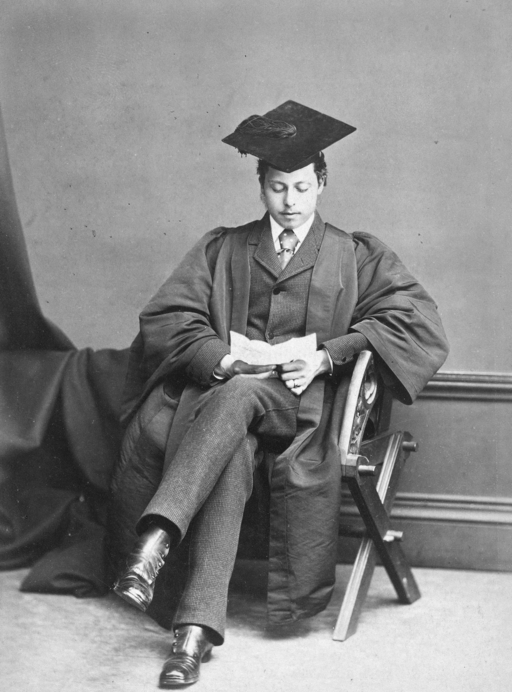

In October 1879 Royalty came to St John’s. Prince Leopold (1853-1884), Queen Victoria’s youngest son, was in Sheffield to open Firth College, a forerunner of the University of Sheffield. The Prince stayed at Oakbrook with the industrialist Mark Firth, who was, as its name suggests, the moving force behind the new college. The visit was reported in the press extensively and with due Victorian deference.

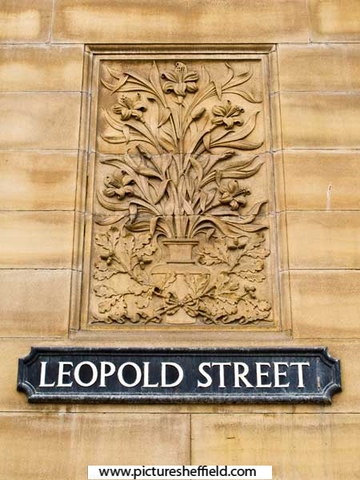

Firth College on the corner of West Street and Leopold Street.

Copyright © Sheffield City Council. All rights reserved. Ref: Picture Sheffield - c03111.

The street sign on the former Sheffield School Board offices.

Copyright © Sheffield City Council. All rights reserved. Ref: Picture Sheffield - c04364.

Leopold is not much remembered today. Leopold Street, in Sheffield’s centre, was named for him but most people probably have no idea of this. He was the only one of Victoria’s children to suffer from haemophilia (she was a carrier, as were two of her daughters) and he died at the early age of 30 after an accident. He was known in his lifetime as an intellectual and had studied at Christ Church, Oxford. Maybe this was why he was invited to open the new college, which was to offer university-level teaching in the town. The Sheffield Telegraph referred to Leopold as ‘England’s Royal Scholar’ and the Huddersfield Chronicle opined:

… the nation has reason to be proud that one of the Royal scions has stepped aside from the engrossing and fascinating pursuits of politics and war, wherein kingly wisdom and valour have scope for exercise, into the quiet walks of literature and science. Prince Leopold studies, observes, and meditates. The love of learning and the cultured taste which distinguished the late Prince Consort have descended to his youngest son, and we have no doubt that if Prince Leopold be endowed with health and strength he will become one of the greatest ornaments of all that is noblest and most exalting in the national life … (Wednesday 22 October 1879)

Portrait of Mark Firth by Thomas Jones Barker. Public domain. 1874.

Oakbrook House, the home of Mark Firth.

Courtesy of Picture Sheffield. Ref: s05492.

There were large crowds when the Prince arrived in Sheffield. He was met at Victoria Station by his host, Mark Firth, along with the Mayor, the Master Cutler and a crowd of railway officials, aldermen and councillors, generally important citizens and various wives, daughters and sisters, all dressed in their best. The station had been specially decorated, with flowers, flags and a red carpet. Ordinary Sheffielders crowded the streets, as the Prince was driven through the town, up to Broomhill and along to Ranmoor, with an escort of police and the Yeomanry Cavalry.

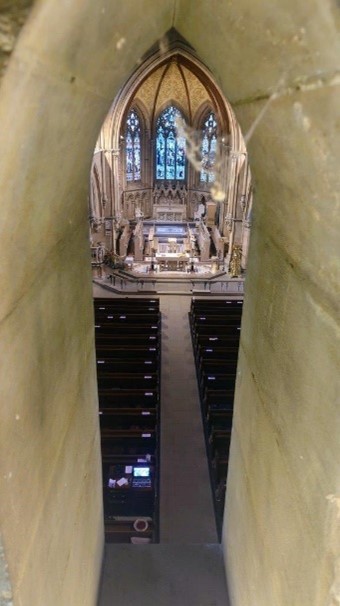

When it came to church on Sunday, St John’s was the natural choice: close to Oakbrook, it was Ranmoor’s own, tall and impressive. Getting there was circumscribed by as much ceremonial as everything else in Leopold’s visit (and probably in his life). Although the weather was not good, ‘rain and wind prevailing during the morning’, many people - thousands, according to the London Evening Standard and Manchester Courier (both Monday 20 October 1879) - gathered to see the spectacle.

‘England’s Royal Scholar’ as an Oxford student. By Hills & Saunders (photographer).

Public domain. Circa 1872

The crowds, however, were most orderly, and appeared to be abundantly satisfied with the sight of the Prince, as he passed to and from the church. His Royal Highness could hardly have anticipated that at such a distance from the centre of the town there would be so many spectators, for he appeared both surprised and pleased; and though, of course, there was no cheering, he frequently raised his hat in acknowledgment of their silent greeting.’ (Sheffield Independent, Monday 20 October 1879)

The police were well prepared.

Inspector Toulson, with one sub-inspector, four sergeants, and 40 constables, was on duty, and distributed the men on the Ranmoor road from Oakbrook to the gates, and they also lined the passage leading from the road to the church. The Chief-constable, Mr. Jackson, was in attendance, seeing that the arrangements were carried out properly.

Many of the people who had met the Prince’s train the day before attended the service, including the Mayor and Mayoress, Mr and Mrs Edward Tozer; the Master Cutler, Joseph Burdekin Jackson; local MP Anthony Mundella; John Newton Mappin, ‘who generously erected the [church] at his own expense’ and his nephews, John Yeomans Cowlishaw and Frederick Thorpe Mappin.

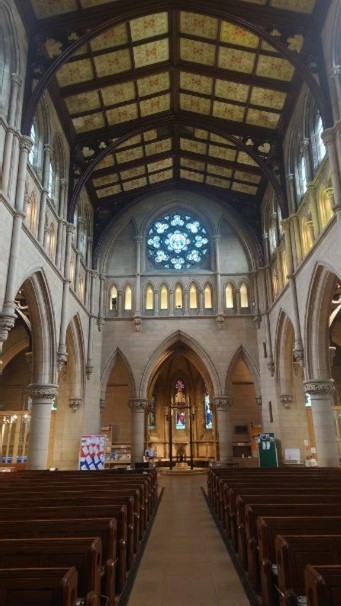

St John’s had been consecrated seven months earlier, in April 1879, and must have looked splendid that morning, even in the gloomy weather. The Illustrated Police News (Friday 25 October 1879) called it ‘a very elegant edifice’. The grounds had been laid out by the designer Robert Marnock, who was responsible for Sheffield’s Botanical Gardens and many of the local estates. The interior decoration was not finished, with the walls and reredos temporarily painted and the large windows with plain, not stained, glass. But in place were the peal of eight bells, the organ, the font of Ancaster stone and marble and the pulpit of wood and bronze, with a crimson velvet carpet leading to it.

St John’s as Prince Leopold would have seen it.

Courtesy of Picture Sheffield. Ref: s02612.

The Telegraph reported that: ‘A few minutes past eleven a murmur of excitement passed through the crowd in the lower road, and immediately afterwards Mr. Mark Firth’s carriage, fully opened, entered at the lower gates, and drove rapidly up to the church.’ At this point Royal dignity was affronted when: ‘The inevitable dog, in the form of a large retriever, of course made his appearance, and ran in front of the carriages a short distance, but then took a turn to the left and bounded over the wall.’ Order restored, Mr Cowlishaw, who was a churchwarden, met the carriages and, carrying his ‘wand of office’, conducted the Royal party to Mark Firth’s pew.

The Telegraph called the sermon, preached by the vicar, the Rev Dr Chalmer, ‘an able and eloquent address’ and, in the fashion of the day, both it and the Sheffield Independent reported it almost verbatim. The text was from Ezekiel xviii: ‘Yet ye say, The way of the Lord is not equal. Hear now, O house of Israel: Is not my way equal? Are not your ways unequal?’

After the blessing, the congregation remained in their seats until the Prince and his party processed out, returning by carriage to Oakbrook. ‘At half-past one o'clock His Royal Highness, accompanied by his suite and Mr. and Mrs. Firth, drove up Manchester road to Mr. Firth’s shooting box on Moscar Moors…’. They returned about six o’clock and a ‘private dinner party was afterwards held, at which one or two friends were present.’ As it was Sunday, there had perhaps been no shooting but rather a good lunch and a walk in the fresh air across the moors.

Leopold’s visit to Ranmoor was remembered by Caroline, the wife of Mark Firth. In her will, signed in May 1893, two years before she died, she left to her second son, Mark, ‘the pendant presented to me by His Royal Highness the late Prince Leopold’.

Val Hewson

21 July 2025

NB Unless otherwise indicated, the quotations in this blog are from the Sheffield Telegraph of Monday 20 October 1879.

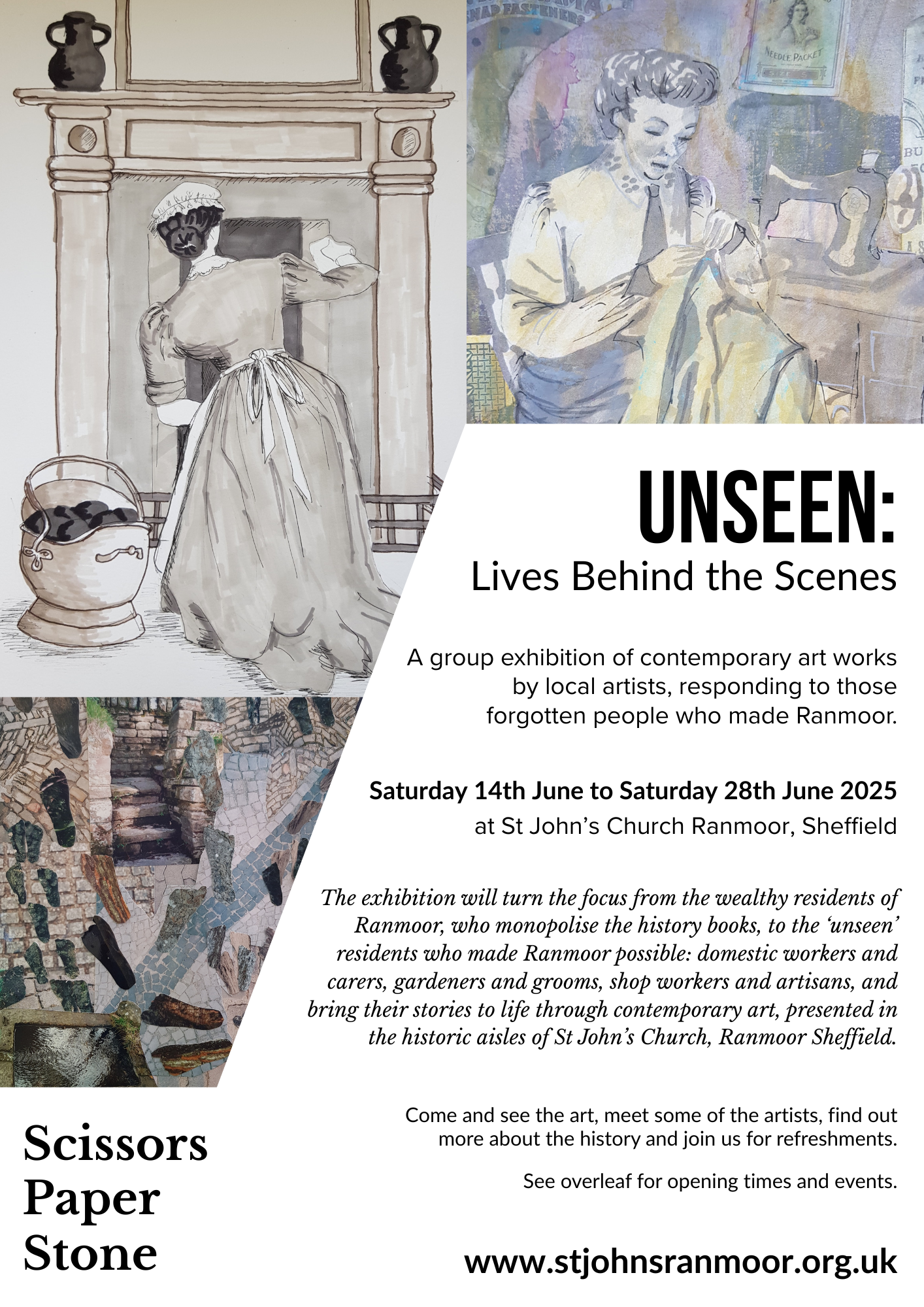

Blog 22 Unseen:

Lives behind the scenes

16th June 2025

Download PDF

‘Unseen’ is an odd title for an art exhibition. Art is something we see, something we look at. But there is more to it. Beyond – through - seeing there is thinking and feeling. Through art we empathise with the experience of others.

Art makes what is unseen seen.

This exhibition is part of the second year of the Scissors Paper Stone project set up to explore the history of St John's and its community. This year, the focus is on the people who lived in the parish towards the end of the 19th century, when both St John’s and Ranmoor itself were still new. What do we see when we look back? We see first the rich and powerful of Sheffield – mainly white men, of course, at that period. We know a lot about them, these men who built Ranmoor’s great houses, who ran Sheffield’s industries and indeed Sheffield itself. Their names are preserved to this day in our streets, parks and art galleries. But important though they were, these people were the minority. Behind them we glimpse the many people who underpinned the lives of Ranmoor’s wealthy few. They are shadowy figures, about whom we know very little. We catch sight of them only occasionally, in an old photo, a legacy in a will or a census return.

And this is what our 'Unseen' exhibition wants to explore. The exhibition turns the focus from the wealthy residents of Ranmoor, who monopolise the history books and archives, to the unseen people who made Ranmoor possible.

• The domestic servants - maids, cooks, nannies, laundresses, gardeners, grooms and coachmen who ran the comfortable homes of the wealthy. Lucy Lethbridge in her book Servants (Bloomsbury, 2013) says that:

‘In 1900 domestic service was the single largest occupation in Edwardian Britain: of the four million women in the British workforce, a million and a half worked as servants, a majority of them as single-handed maids in small households.’

• The workers in the steel mills, factories and breweries who generated the wealth for the lavish villas all across Ranmoor.

• The miners who dug the coal to power the factories and heat the houses.

• The farmers who grew the crops and produced the food.

• And those who transported materials and goods on the railways, roads and canals.

Victorian society would not have thrived without the hard labour of these unseen people.

And there are yet more unseen whose lives are reflected in the exhibition. People in the colonies who would have used Sheffield’s steel to grow and process the sugar, the cotton and the tobacco or to mine the valuable raw materials that helped make the British Empire so rich.

Our artists – all 19 of them – have responded in very different ways to these issues, including through artforms and crafts that unseen people used to express themselves and their creativity - embroidery, patchwork and rag rugs. These creative arts were not considered ‘proper’ art and were often dismissed as ‘just women's work’. (In some circles, they still are.) Yet they required as much skill and artistic judgement as an oil painting or watercolour.

Complementing the artworks there is ‘Kitchen Unseen’: a display of the vintage recipe books that might have been found in Ranmoor’s Victorian and Edwardian houses, great and small.

By reflecting on the lives of the unseen Victorians, we hope that the artworks will make visitors to the exhibition think about the unseen people of today. The people on the edges of our society, people who are old, sick or have a disability, who are poor or unemployed or homeless. Cleaners and carers. Those trapped in modern slavery or working in terrible sweatshops and the like across the world, to provide us with cheap goods and such a high standard of living. Their voices go unheard, their needs unmet, their lives unseen.

Art helps us see more clearly, and reflect differently, on the present as well as the past. Come and see the 'Unseen'.

Margaret Bennett

12 June 2025

Blog 22a

A Pie and a Pint with the Residents of Ranmoor market c.1880-1919

With Jane Bartholomew

Download PDF

Blog 21: ‘A 5,000-hr. labour of love’: The kneelers of St John’s

7th May 2025

Download PDF

As many of you will have noticed you can now sit down in a pew with only one kneeler at your feet. Over the years our precious kneelers have piled up around us, most no longer used. In order to make it easier for us to keep the church clean, we have placed the more elaborate kneelers in the nave of the church and put the plainer ones in the side aisles. Many with an affection for a particular kneeler have taken it home, donations having been put towards the spire fund.

Who made these kneelers? Who learnt the art of when to use a ‘Florentine stitch’ or an ‘Hungarian Diamond’? And what inspired the creation of over 300 tapestries, each one unique? Many of these tapestries are initialled, so occasionally we can identify the embroiderers who created them, but all too often they are unclaimed and their makers unidentified.

As the Scissors Paper Stone community project unfolded this year, we realised that not only do the numbered pews we fill connect us with men and women whose rental payments are in our map of 1890, but the kneelers at our feet connect us with the parishioners who made them.

Though kneelers have been made in Britain from the seventeenth century onwards, parish production didn’t get going in earnest till after the Second World War. Visit Wadham College in Oxford to discover the first politically sensitive kneelers, stitched in honour of the Stuart dynasty and commissioned in the early seventeenth century by Stuart sympathiser, Dorothy Wadham. Thanks to the accession of the Hanoverians a hundred years later, the Stuart coat of arms made these kneelers politically suspect. Because they were tucked away in an archive these sumptuous works have survived in almost their original glory.

For the last fifty or so years, our kneelers have been used by thousands and are witness to the craftsmanship rather than the political beliefs of their makers. Though some of them have worn at the seams, most still look crisp and clean, thanks to the efforts of our cleaning teams over the decades. The wealth of imagery is extraordinary. Who made this predatory whale and the balletic Jonah? And this commanding eagle, the symbol of St John the Evangelist? (Perhaps with a worm in its mouth?)

Pauline Heath and Rowan Ireland have photographed a huge number of our kneelers which we will send to the Kneeler Archive, set up because nationally kneelers are going out of use.

Explore: https://archive.parishkneelers.co.uk/

The theme of this year’s Scissors Paper Stone exhibition is ‘Unseen’. Local artists are responding to the lives of the people who maintained the life-styles of St John’s pew-renters in the nineteenth century. The parishioners of St John’s who created our kneelers are almost as unseen as these nineteenth century domestic workers. Sadly, we have no record of their names and the kneelers they made.

We do know that there were two particularly productive groups of kneeler-makers: one in the 1970s led by Pam Booker and Sadie Lockwood and the other in the early 2000s led by Eileen Stirling.

David Booker has shared with me information and photographs that help us get a sense of the first kneeler project. The report about the project in July 1974’s Sheffield Telegraph, was entitled ‘A 5,000-hr. Labour of Love’. It opens with the proud declaration that ‘Sore knees are a thing of the past at St John’s Church, Ranmoor, Sheffield.’

The photograph shows on the left David’s mother, Pam, who organised the creation of 100 kneelers and on the right Mrs Sadie Lockwood of Caxton Road Ranmoor ‘who designed the motifs’. I have been unable to learn much about Sadie but we have another monument to her craft and design skills in the church. To the right of the vestry door is her magnificent tapestry commemorating the burning of our first church in 1888. She was clearly a highly skilled embroiderer or ‘broderer’.

Pam Booker was not only a skilled needle-woman, she also had the great gift of enabling people to work together. She built up a team of people partly because of her own sociability. Pam had, since the death of her husband, brought up her two sons on her own. Her husband had survived four years in a German Prisoner of War Camp during the Second World War but he died of Hodgkins disease in 1955. Supported by her brother and sisters, Pam lived in Fulwood and was a devoted mother of David and Keith. She was a member of St John’s, welcoming people into her home for all kinds of social gathering. The making of kneelers brought many women together.

The second wave of kneelers flooded our pews at the beginning of this century, when Alison Wragg, our assistant priest, was given a kneeler kit by her dear friends Doreen and Ted Bales. Alice Underwood was a member of Eileen Stirling’s team. Alice remembers,

I did a scene of a bird on blossom, if I remember right - using a picture in one of my embroidery books (The Country Diary Book of Crafts). I think this was crab apple blossom.

The images were generated in all sorts of different ways. Some were personal and some from a booklet called Church Hassocks by Designers Forum. ‘Broderers’ were encouraged to put their initials on the side. Most worked from home rather than in groups.

The famous Winchester Cathedral embroidery project 1931-1938, celebrated in Tracy Chevalier’s novel A Single Thread, was apparently a highly organised but social affair. Unsatisfactory work was to be unpicked and colours used were carefully monitored. The inspiration for this project was the gifted Louisa Pesel, from Bradford. She served as the director of the Royal Hellenic School of Needlework and Lace in Athens, Greece, from 1903 to 1907. Her career was brought to a halt by the need to care for her elderly parents in Bradford. When they died she was able to resume her nurture of the nation’s embroiderers. Her imagination and practical skills were an inspiration to all those who worked with her, many of whose lives, like hers, were to a certain extent circumscribed by domestic duties.

Elizabeth Bingham has collected images of kneelers across the country. Her book, Kneelers: The Unsung Folk art of England and Wales (2023) will eventually find its way into the St John’s Library. It is full of tranquil images of what she calls ‘The Pleasures of Peacetime’: footballers, fishermen, steam trains and my favourite, a slip road on to the A14 to be found in All Saints Sproughton. Do explore the history of this craft which has been part of the tapestry of our spiritual lives for so long.

Mary Grover

5 May 2025

Blog 20: Pew Renting: the last shall be first and the first last

22nd April 2025

Download PDF

Many of you will never have heard of pew renting because quite rightly it is a thing of the past. But until after the Second World War it was often used to raise money to pay for the priest and the church fabric. In medieval times such a system was not necessary because church costs were covered by the tithing of the whole parish. Every resident, devout or not was required to pay a tenth of their worth, whether in goods or money. This was often resented but as a system it sort of worked until the Church of England lost its monopoly on Christian observance. In the seventeenth century onwards, Quakers, Methodists and Catholics rightly objected to supporting a creed they did not believe in. So it seemed fair enough to ask those who actually came to church to pay for its upkeep and staff. Anglican and some dissenting congregations adopted the pew renting model.

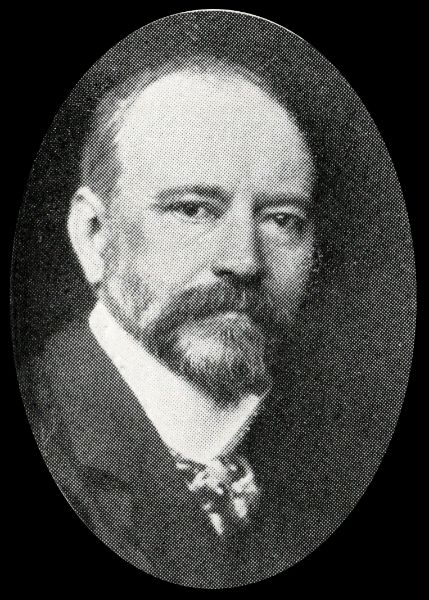

But if you look at the pew renting map you will discover the flaw in this new system. How, in heaven’s name, did the vicar, the Reverend JG Williams, described as a ‘genial’ man preach on Christ’s words recorded by Matthew, that ‘the first shall be last and the last shall be first’ when in front of him were four of the richest steel manufacturers in the city and in the furthest corners of the church, their servants? I don’t know how long St John’s used the pew renting system but most churches had abandoned it by the beginning of the twentieth century. Thank goodness for that but, I am afraid I have to be grateful that thanks to this hierarchical and profoundly unchristian practice we have in front of us just the kind of document that we needed to identify those residents of Ranmoor who, like the stone masons, left few traces of their lives. For though this map has, at its centre, the names of the wealthy, it graphically illustrates the diversity of the congregation and the fact that the majority of the men and women in front of Reverend Williams were not as rich as our early benefactors, Henry Steel, Frederick Thorpe Mappin or Robert Colver.

On the attached map you will find the names of all those who rented a pew in St John’s in 1890. The number in brackets indicates the number of ‘sittings’ they paid for. You’ll notice too, that some of our more illustrious predecessors rented two lots of sittings – one for the family and the second for their servants. The north aisle lies largely unrented – this, the colder side of the church, would have been the seating for those who hadn’t rented a pew.

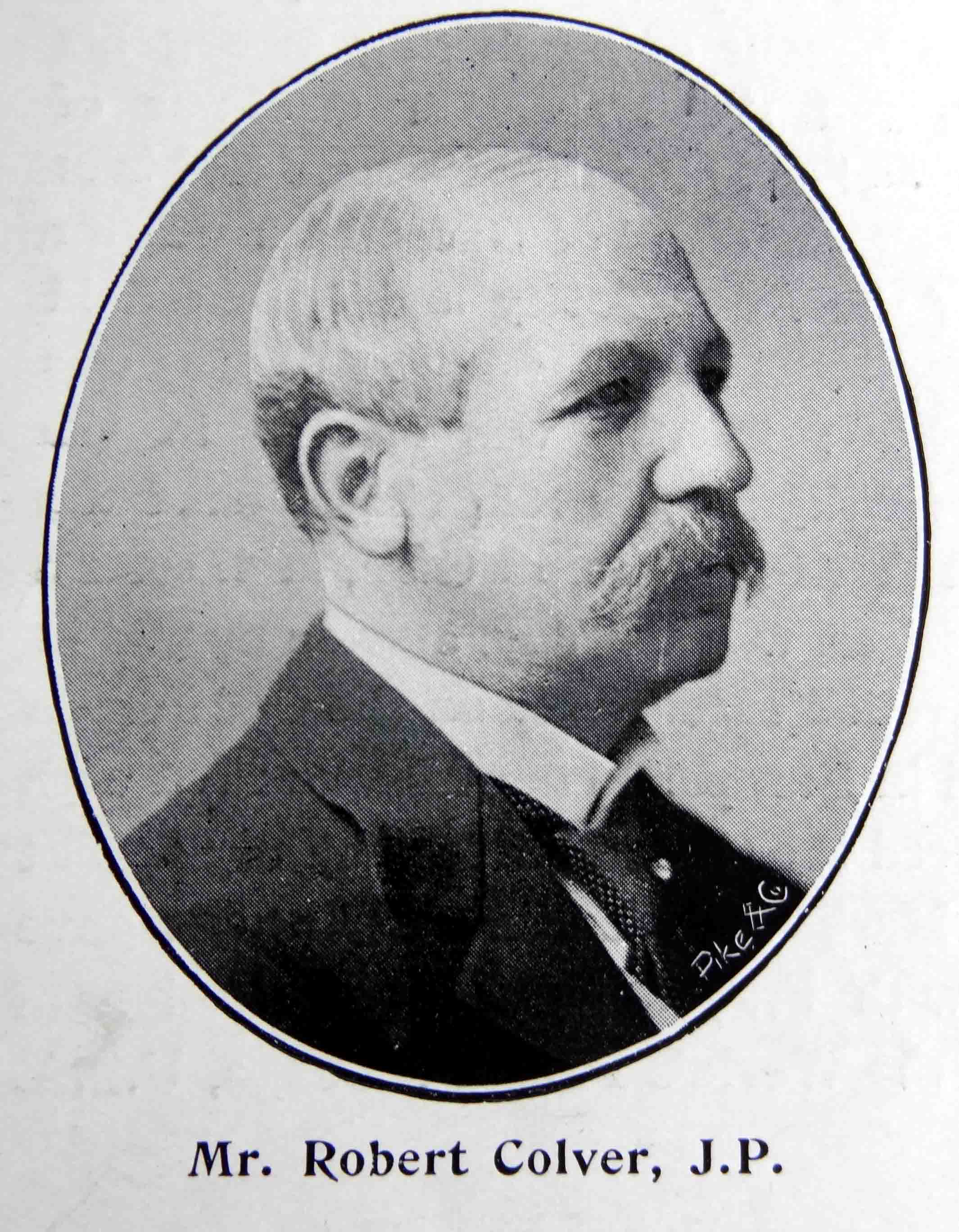

Below are the brief profiles of two of our most prolific pew renters, Robert Colver (pews 42 and 20) and Samuel Earnshaw Howell (pews 35 and 7).

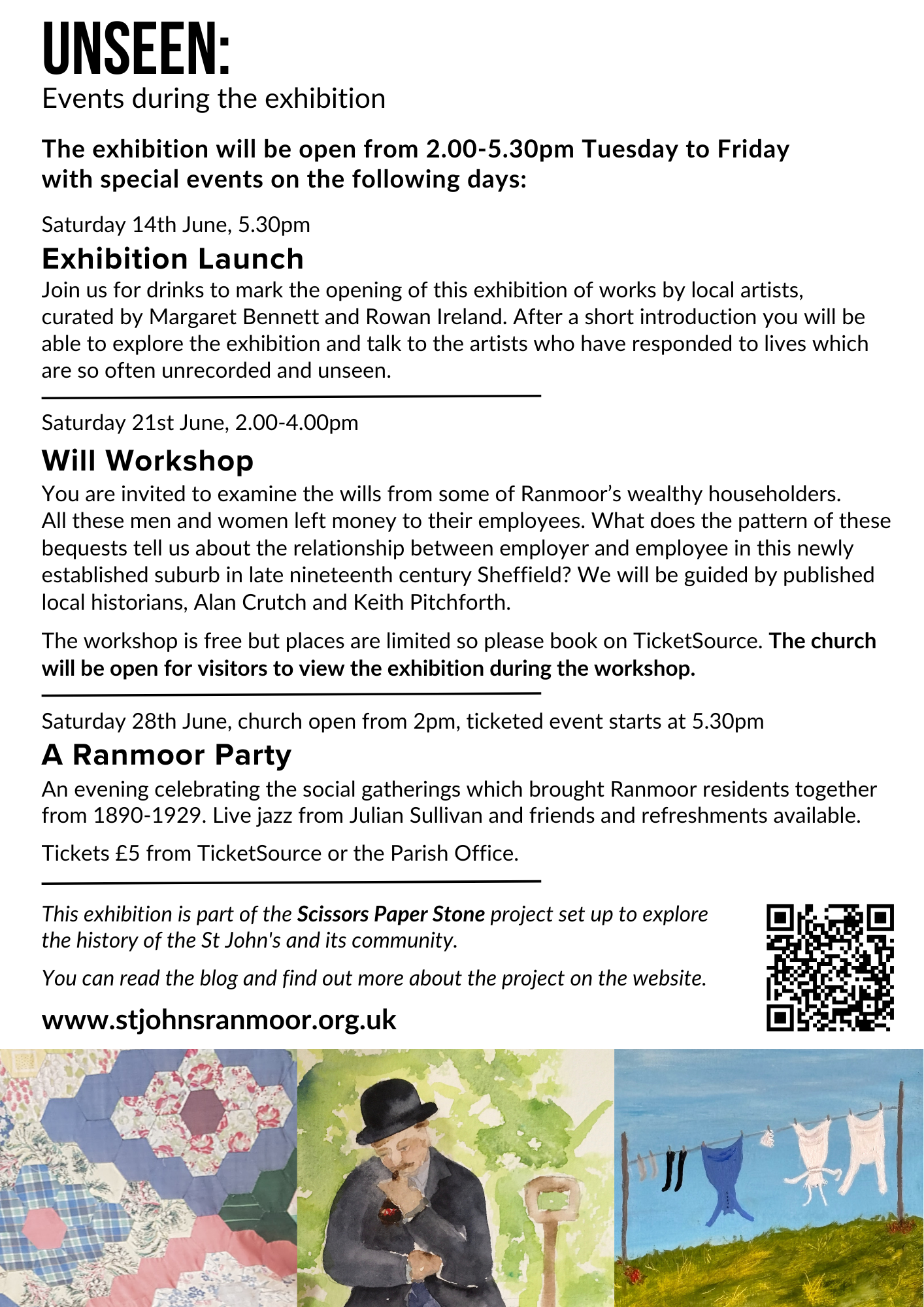

Robert Colver (1842-1916)

Robert’s father was a builder and contractor and he was educated at Milk St Academy. He chose not to join the family business: he became a farmer & land valuer through his connections to his mother’s farming family. He acquired his own farm in Ecclesfield at the age of 21. However, in 1873 he changed direction and went into partnership with Joseph Jonas, steel manufacturer, who had started the Continental Works in Sheffield. The company expanded and eventually manufactured all kinds of steel, from watch springs to heavy projectiles and high class tool steel. He was church warden at St Johns and took an active interest in the rebuilding of the church. He was much involved in the life of the city: a member of the Chamber of Commerce, a J.P. from 1910, a Freemason, committee member of the Sheffield General Hospital & Dispensary, an active supporter of the Ranmoor Horticultural Society. He joined the Company of Cutlers in 1882 and became Master Cutler in 1890. Two of his sons were killed on the First World War and the remaining son, Robert Colver junior, joined the family firm.

He died at Rockmount in 1916; the funeral service was at St John’s, the internment at Fulwood Church. He left £243,530 in his will.

(Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 4th December 1916)

Samuel Earnshaw Howell (1847-1928)

No pew for his servants but they were not forgotten.

Howell and Co., originally a steel and file maker in the Wicker, was founded in 1853. He lived at 14 Gladstone Rd. The Hawley Collection website describes the development of the family firm:

‘One of the partners, John Bennett Howell (1818-1904), launched his own business. By 1880, it had two locations: Brook Hill Steel Works, Brook Lane (which dealt in steels and tools); and Sheffield Tube Works, Wincobank (which specialised in tubes for locomotives and steam engines). J. B. Howell’s son – Samuel Earnshaw Howell (1847-1928) – joined his father in 1870. Samuel was Master Cutler in 1888, and became a JP, Conservative town councillor, and president of the Sheffield Chamber of Commerce.

The problem of corrosion in steam tubes meant that Samuel became keenly interested in rustless steels. After stainless steel’s discovery in 1913, Samuel Howell became ‘an early convert to stainless ... [and] … was one of those who contended that an efficient cutting edge could be obtained with stainless knives’ (Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 16 April 1928).

Samuel E. Howell died on 15 April 1928 at Sheffield Royal Hospital, after he was knocked down by a tramcar at Nether Green terminus (Sheffield Independent, 16 April 1928). The funeral service was at Ranmoor, followed by cremation at City Road. He left £86,914.’

Few were more generous to their servants than Samuel Earnshaw Howell.

Mary Grover with map designed by Sarah Beardsmore

14 April 2025

Blog 19: Ranmoor's lost Church (Part 3) -‘An Ornament to the Neighbourhood’

7th April 2025

Download PDF

Here Val Hewson looks at what happened after fire destroyed the beautiful church John Newton Mappin had given to Ranmoor.

When the church of St John the Evangelist was consecrated in April 1879, the weather had been dull, and it was icy when fire swept through the church in January 1887. On 28 July, just seven months after the disaster, the weather was ‘thoroughly summer-like’ for the ceremony to lay the foundation stone of a new church. On that Thursday afternoon, ‘an imposing gathering’ of parishioners, clergymen and guests came out to watch Mrs Charles Henry Firth lay the stone. Ranmoor was still a fairly new suburb in the late 1880s, and the grand church donated by John Newton Mappin was a focus for the community. The fire had been a shock, and people wanted to see the new St John’s. How would it compare? Would it be as beautiful, as richly decorated, as worthy of Ranmoor as the first church had been?

The first Church

The first Church

The foundation stone, all two tons of it, is set into the church’s southern wall, well above the ground, at the point where the chancel meets the nave. A ‘spacious platform plentifully bedecked with bunting’ was erected, with room for the dozen or so people involved in the ceremony. There must have been steps up, since Marianne Firth, presumably tightly corseted in the tailored costume and bustle of the day, would hardly have scaled a ladder. The clergymen, in cassocks and surplices, might also have been grateful for steps. The choir stood before the platform, and the guests clustered all around.

As the ceremony started, the vicar’s son, three-year-old James Tweedie, ‘presented Mrs Firth with a handsome bouquet’. The choir, ‘with hearty assistance from the spectators’, sang a specially composed hymn. The Gospel was read and then Rev Tweedie spoke about the new church. He explained, to a round of applause, that it would be bigger than the old, to accommodate Ranmoor’s expanding population, but there would be

as much as possible in the new building to remind them of the old, and to show that it was still the Church of St. John the Evangelist which they owed to the liberality of the late Mr. John Newton Mappin.

The architect Thomas Flockton then announced that, as was the tradition, various documents had been sealed in a bottle and placed beneath the foundation stone. There were copies of the day’s Sheffield newspapers, a history of the church written by Rev Tweedie and a record of the ceremony. This last read:

The stone above this, being the corner stone of the Church of St. John the Evangelist, was laid by Mrs. Charles Henry Firth, of Riverdale, on Thursday, July 28, 1887. Archibald George Tweedie, MA, vicar; Robert Colver and Hamer Chalmer, wardens. Architects, Flockton and Gibbs; builders, William Bissett and Sons. The church which was built upon this site in the year 1878 was so far destroyed by fire on Sunday. January 2, 1887, as to necessitate the complete rebuilding of all parts except the tower and spire.

John Yeomans Cowlishaw presented a ‘beautiful silver trowel, ivory handled’ to Mrs Firth. It was fitting that he, a nephew of John Newton Mappin, should play a role. He said that he could not help but think of his uncle, who had died in 1883. The inscription on the trowel read:

Presented to Mrs C H Firth on the occasion of her laying the foundation stone of the Church of St. John the Evangelist, Ranmoor July 28th, 1887.

Marianne Firth, who performed her task ‘in a very graceful manner’, announced: ‘I lay this foundation stone in the name of the Great Jehovah, the Holy, Holy, Holy, undivided Trinity, Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, Three Persons but One God, Blessed for Evermore.’ She then looked to see if the stone was plumb and added, ‘I pronounce this stone to be well and truly laid.’ The spectators applauded again and the churchwardens, Robert Colver and Hamer Chalmer, proposed a ‘hearty vote of thanks’. ‘

The National Anthem was sung [and] the bells in the tower rang out a merry peal.’

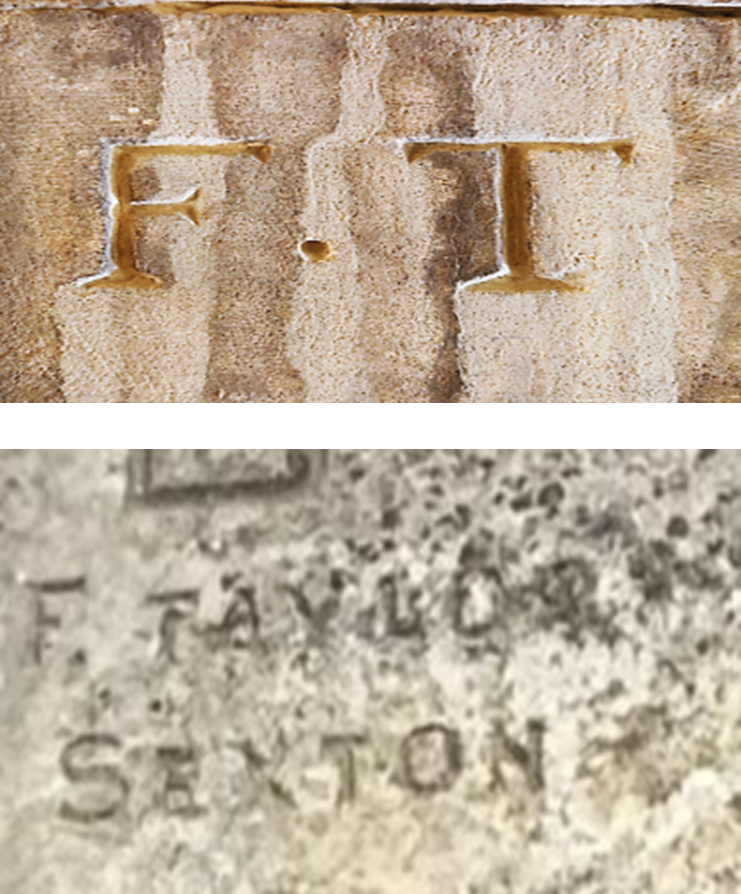

The foundation stone

The foundation stone

Why was Marianne Firth chosen for the honour of laying the stone? Her husband explained that his wife ‘took very great interest in the church and the parish generally’ when he – not she! – acknowledged the vote of thanks. No doubt this was so. Charles Henry and Marianne worshipped regularly at St John’s, and he had presented the organ for the first church in 1879. But there was probably more to it. In terms of business, wealth and philanthropy, the Firths were after all Ranmoor royalty. On this occasion, Charles Henry and Marianne were joined by the Edward Firths and the Branson Firths, Charles Henry’s brother and eldest son respectively.

The next day’s Sheffield Telegraph elaborated on Mr Tweedie’s description of the new church:

The new church - from a print hanging in the entrance of the Ranmoor Parish Centre

… nave, north and south aisles, ante church or corridor at the west end with baptistry, chancel with chapel on the south side and organ chamber on the north, and vestries. The tower, with spire, which was uninjured by the fire, will form the principal entrance as before, and there will be two other doors for exit, one near the west end and the other near the east end. The style of the building will be geometrical English of a severe and bold type … The chancel will be semi-octagonal in form at its eastern end. The interior of the church will not be open to the roof as has been lately been the fashion in churches, but will be ceiled over at about the level of the eaves, thus leaving a space in the roof … which will contribute materially to the warmth … a series of open arches forming a triforium, which will add very much to the internal effect. Behind these arches … will be hot water pipes … so avoiding the draughts which are frequently caused … The number of sittings is 759, being an increase of 240 over those formerly provided.

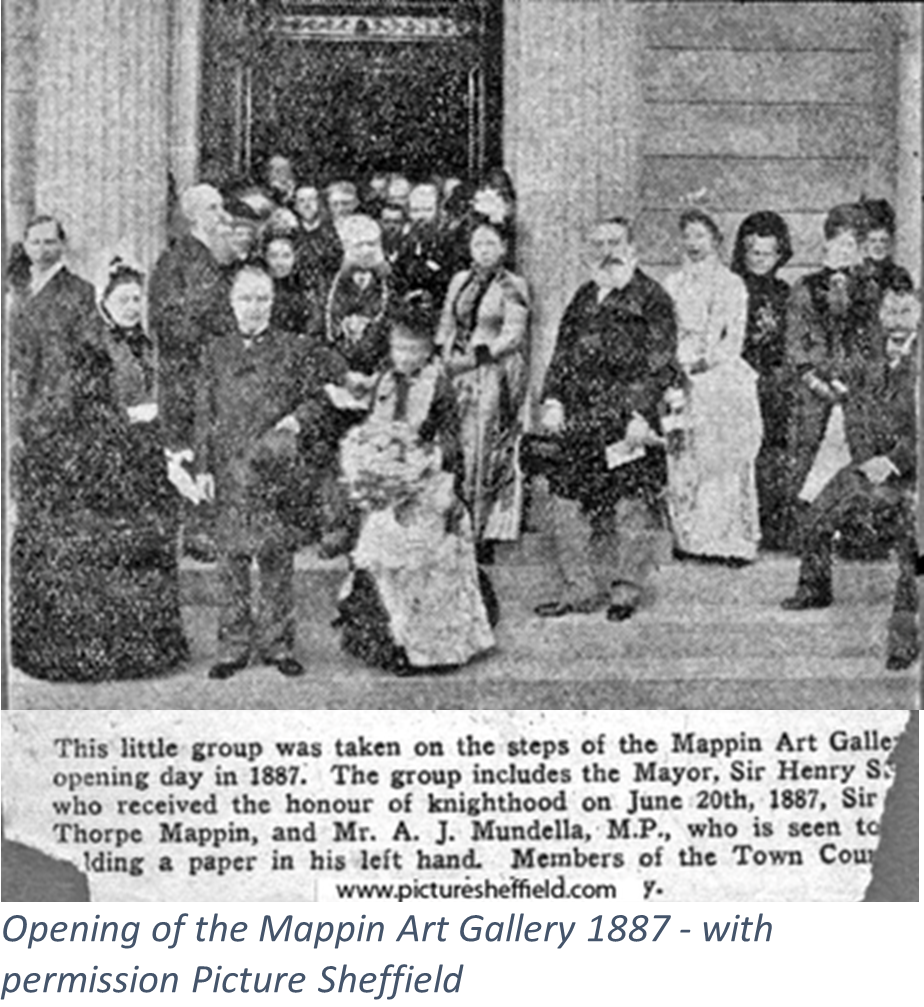

The new church was designed by Edward Mitchel Gibbs, in partnership with Thomas Flockton, and was being built by William Bissett and Sons. Both were then among Sheffield’s most sought-after contractors, and so their involvement in a prestigious project like St John’s was to be expected. In fact, they all had in a sense a personal interest. Edward Gibbs had been the architect for the first church, which he had watched burn down. William Bissett and his wife lived near St John’s, at Rock Mount on Fulwood Road. Flockton, Gibbs and William Bissett’s sons, William junior and Lawrence, were all at the ceremony, no doubt to make sure everything went to plan. On that sunny afternoon in 1887, they must all have felt confident in the future. Was not St John’s going well? Had their celebrated Mappin Art Gallery not been officially opened just the day before? Flockton and Gibbs did of course win further renown, but it was different for the Bissetts. After William senior died in 1889, the business went bankrupt (with its losses apparently including £1,800 on St John’s). Lawrence and William absconded with company funds, never to be seen again in Sheffield, and their brother John, who knew nothing of their peculation, was left to cope alone.

But back to St John’s. The first service in the new church was held on Sunday 9 September 1888 – apparently later than had been hoped but there had been delays due to bad weather. There was of course a large congregation that Sunday morning, probably including most of the people who had watched Marianne Firth lay the foundation stone fifteen months earlier. ‘The beauty of the church and its noble proportions were greatly admired; and Messrs Flockton and Gibbs, its architects, who were at the morning service, were warmly congratulated by many.’

It remained only for the finances to be finalised. Archdeacon Blakeney, who preached the sermon, said, with some humour but hinting at earlier dissension:

… an ornament to the neighbourhood, and which will be in harmony with the palatial residences which surround it. I know that some people felt that a less pretentious and less expensive structure would do. Well, it might have done, but then you would not have felt the same interest in it, or taken the same delight … Everything about the church is good, is substantial, is handsome … I feel satisfied that there is not a person connected with the church who would now wish to see the work that has been accomplished done in a less costly manner.

According to the churchwardens, the new church cost £13,700. They had £9,400 insurance money for the old church. It is difficult to follow the trail 140 years later, but it seems that, thanks to the efforts of the churchwardens and vicar, the remaining £4,000 or so was raised through donations from parishioners and others. The newspapers reported, for example, that at the first service the collection was around £300. By the early months of 1889, the debt was all cleared, and the congregation could, in Archdeacon Blakeney’s words, ‘really call the church [their] own'. St John’s was, the vicar claimed, ‘the handsomest modern church in the West Riding of Yorkshire’.

Val Hewson

7 April 2025

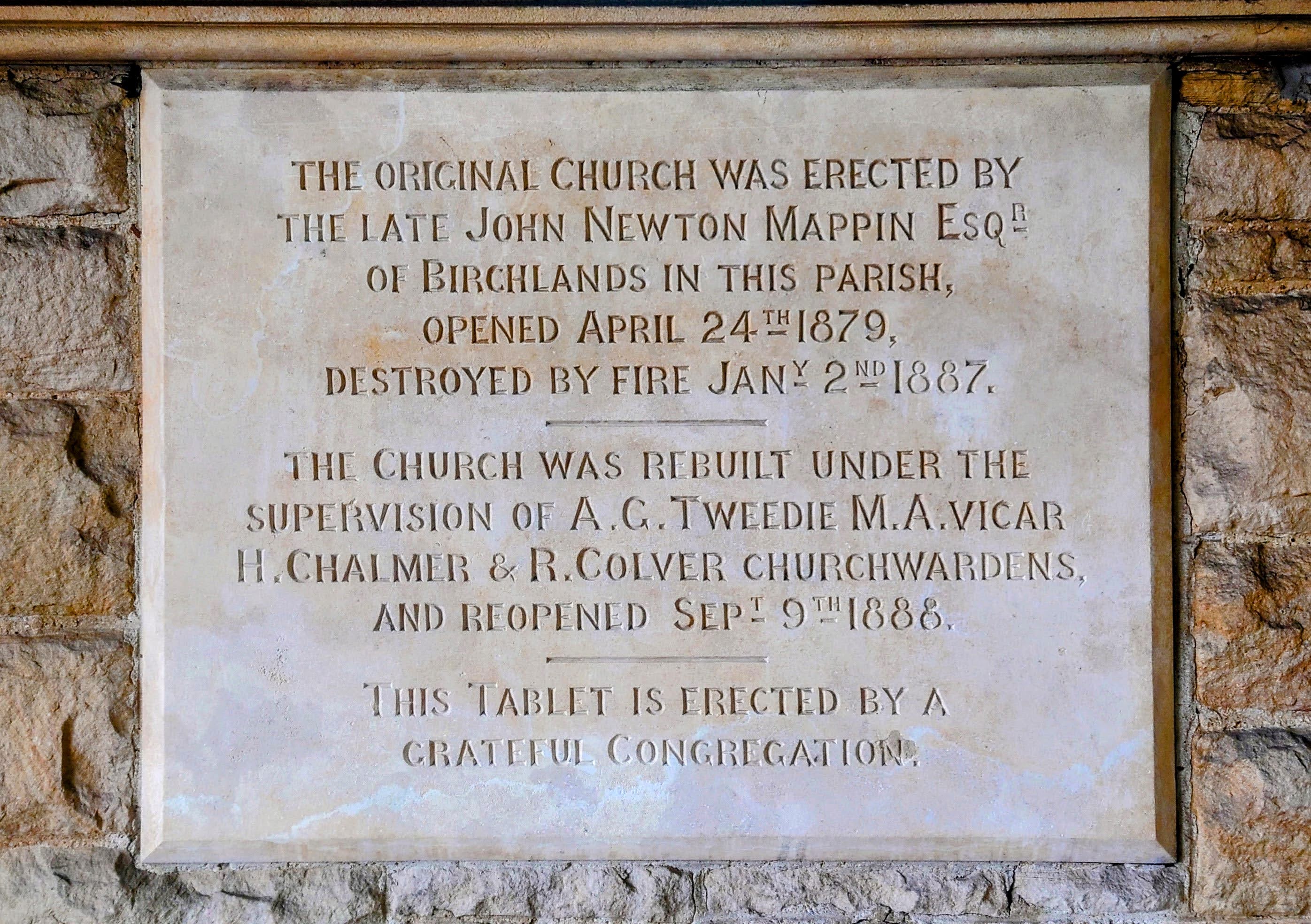

The plaque in the church porch, thanking Mr Tweedie, Mr Chalmer and Mr Colver.

The plaque in the church porch, thanking Mr Tweedie, Mr Chalmer and Mr Colver.

Note: The many quotations above come from various Sheffield newspapers from July 1888 to April 1889. I’ve not included exact references as I think they break up the text, but if anyone is interested, please email val383@btinternet.com. The vicar’s history of the church, although not long, is too much to include above, but again do email if you would like to see it.

Blog 18: Ranmoor's lost Church (Part 2)

13th February 2025

Download PDF

‘Today its place knows it no more’

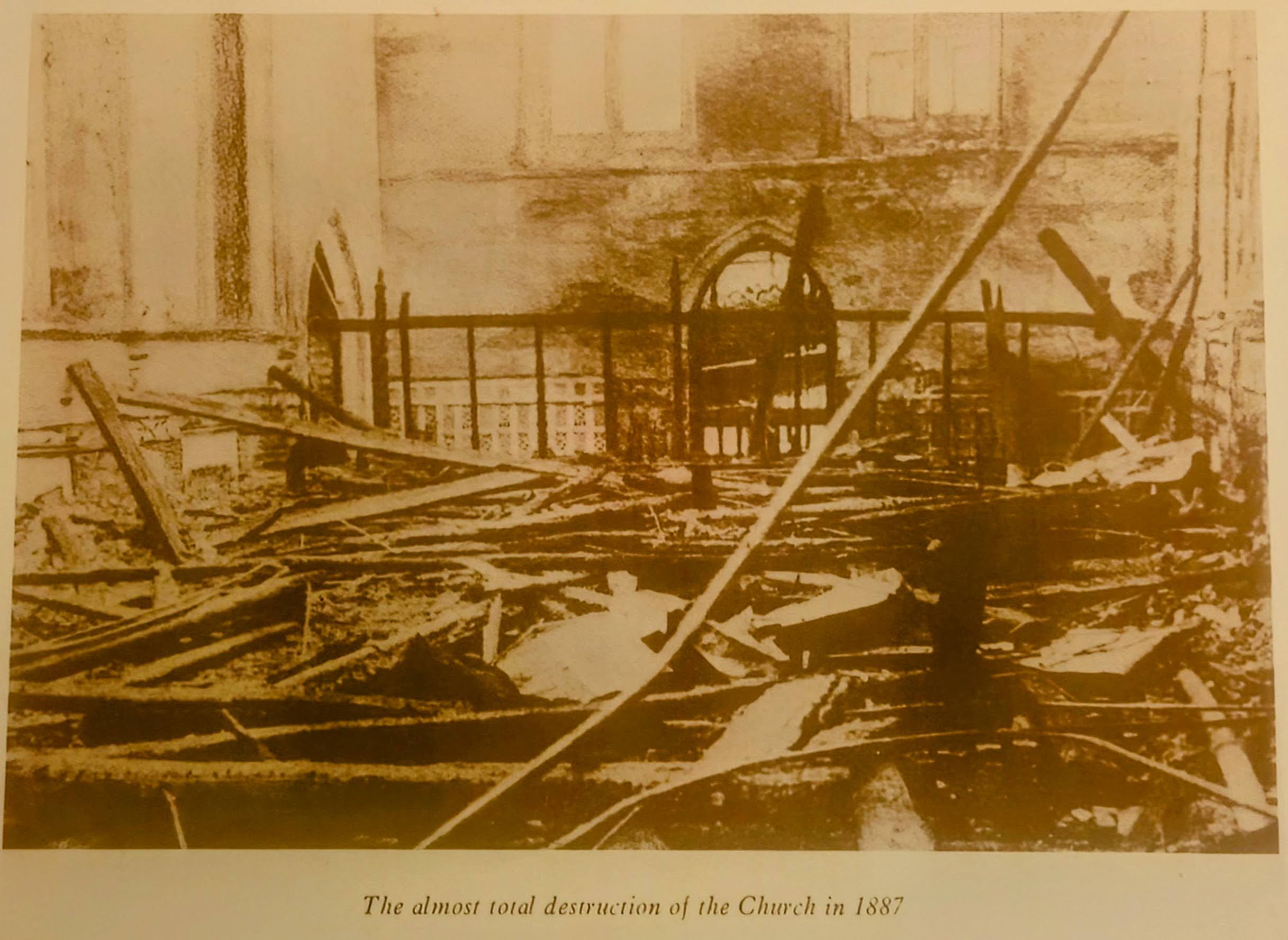

Val Hewson wrote in January (Blog 16) about the first St John’s, given by John Newton Mappin to Ranmoor in 1879. It was once described as ‘the Church of the wealthy’.* Its furnishings were elegant: a pulpit of bronze and wood, a font of Ancaster stone and marble, Brussels and velvet pile carpeting, Minton floor tiles and more. But just seven years after the consecration all this was lost.

The Church of St. John the Evangelist … was wreathed in flames from the chancel to the western gable, from the organ chamber to the southern porch … as the fierce heat burnt away the timber, the loosened tiles dropped into the interior, and through the roof protruded tongues of fire … The interior was one seething mass, which outlined the architectural features of the building … very soon the great volumes of black smoke, lit here and there by lurid gleams from the nave, told to Ranmoor that its church was doomed.**

The alarm was given by the caretaker Thomas Leighton around 9.30 on Sunday morning. It was 2 January, the first Sunday of 1887, and there was a severe frost, making roads and paths treacherous. In the big houses around the church, servants would have been serving breakfast, and masters and mistresses eating eggs, bacon, kidneys, kedgeree, toast and marmalade. Poorer people would not have eaten so well but were probably looking forward to their Sunday rest. Some would already have been getting ready for church and others feeling a little sorry for themselves after New Year celebrations.

St John's Before the fire (Picture Sheffield Ref s02612)

Leighton, ‘anxious that the church should be warm’,* had kept a fire burning in the furnace all night. This was the custom in winter. The caretaker, about whom we know only that he was living in Upper Ranmoor Road, had started work at about 5am, to get everything ready for Sunday services. Down in the cellar he ‘”fired up,” got the furnace at a good heat, and at eight o’clock left everything apparently safe’.** He spent half an hour setting out the communion service in the church and went home for breakfast around 8.30am. When he came back almost an hour later, it was to the smell of burning wood and smoke ‘creeping through the roof of the organ chamber’.** He hurried through the vestry into the church.

The flames were bursting out all about the top of the organ pipes, creeping inch by inch lower, whilst forks of fire shot up against the arching, and curled upwards into the roof of the church.**

Leighton kept his head. He ran down to the Ranmoor Inn from where a messenger rode off at a gallop to the police station in Spooner Road, Broomhill. Here at 9.50am a call was made to the ‘Fire Office’ in Rockingham Street. The horse-drawn fire engine raced the two miles uphill to the church, arriving at 10.10am. Inevitably some spectators complained of a slow response, but the Telegraph dismissed this: ‘… certainly not justifiable, for Superintendent Pound was present twenty minutes after receiving the call, which is capital time on a frosty road from the fire engine station’.** The small ‘hose cart’ kept by the Broomhill police had arrived just before and started drawing water from a nearby hydrant.

Meanwhile Thomas Leighton had run up Ranmoor Park Road, to the vicarage, shouting ‘Mr Tweedie, the church is on fire.’** The churchwardens, Hamer Chalmer and Robert Colver, came hurrying along. The industrialist John Bingham and his son Albert, who lived across from the church at West Lea – now the parish centre – came out too.

City of Sheffield Fire Brigade at their Rockingham Street Station (Picture Sheffield Ref: u11211)

The vicar succeeded in getting into the vestry, and peeped through into the church. The east end was then almost in total darkness. There was such a dense volume of smoke … Looking towards the west Mr. Tweedie could make out the familiar objects of his church, but only dimly. To enter the church and save any of its contents was out of the question; all Mr Tweedie, Mr Bingham and the other gentlemen who gathered round the doors could do was to carry off some of the furniture of the vestry, together with the books and registers from the safe, the alms dishes, and the portion of the communion service not set out on the altar.**

Meanwhile, Thomas Leighton bravely made his way to the gas meter to ‘turn the tap off. He was nearly choked by the smoke’, but was successful and ‘locked the gas chamber behind him’.**

As the men watched, One by one the windows were blown out with a sound like small artillery, the memorial windows going in the common ruin. Then the roof began to fall as the smaller beams burnt out. The large west window fell outwards with a great crash, and behind it came a great volume of smoke …**

While there were reports of parishioners arriving for the service, unaware of the disaster, word seemed to have spread quickly. Given the church’s location, this is no surprise:

Soon the roof fell in, and the nave was a vast furnace, the flames and smoke from which were seen from the hills of Ecclesall, Sharrow and Crookes, and the village of Fulwood.*

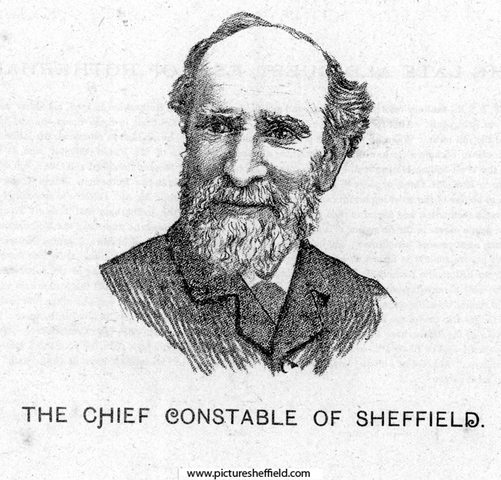

Chief Constable John Jackson (Picture Sheffield Ref s08336)

People were gathering, including ‘a great number of influential citizens and inhabitants of the district’.** The Chief Constable, John Jackson, on his way to St Mark’s Church, came instead to Ranmoor, and Inspector William Toulson of Broomhill had to manage not only the hose cart but also crowds. Everyone was affected by the ‘sorrowful scene’** but none more so perhaps than Edward Mitchel Gibbs, who had designed the church, and John Yeomans Cowlishaw and Frederick Thorpe Mappin, the nephews of John Newton Mappin.

As soon as he arrived, Superintendent Pound realised that the nave and the chancel were beyond saving. There was a chance, he felt, for the tower and spire, which were slightly apart from the church, and so he directed water there. To the bystanders it must all have been terrifying, and Frederick Mappin ‘felt it his duty to caution the firemen to be careful in their work’.**